Infrastructure

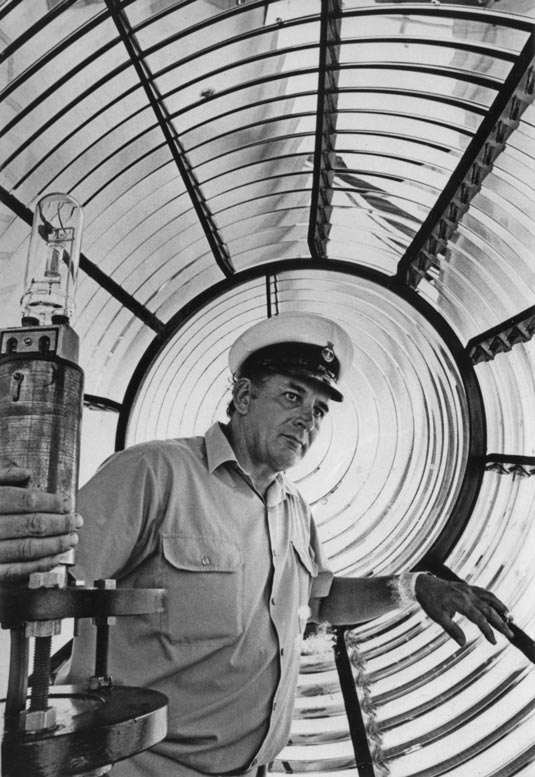

THE “OLD JETTY”

By the mid 1880’s the Byron Bay area was becoming settled with the land being cleared to produce crops and raise animals. Timber was still being extracted for export and loaded from the beach. The town had been gazetted and blocks were made available to build on. The farmers, cedar-getters and the merchants began lobbying the government to establish a port to service the area.

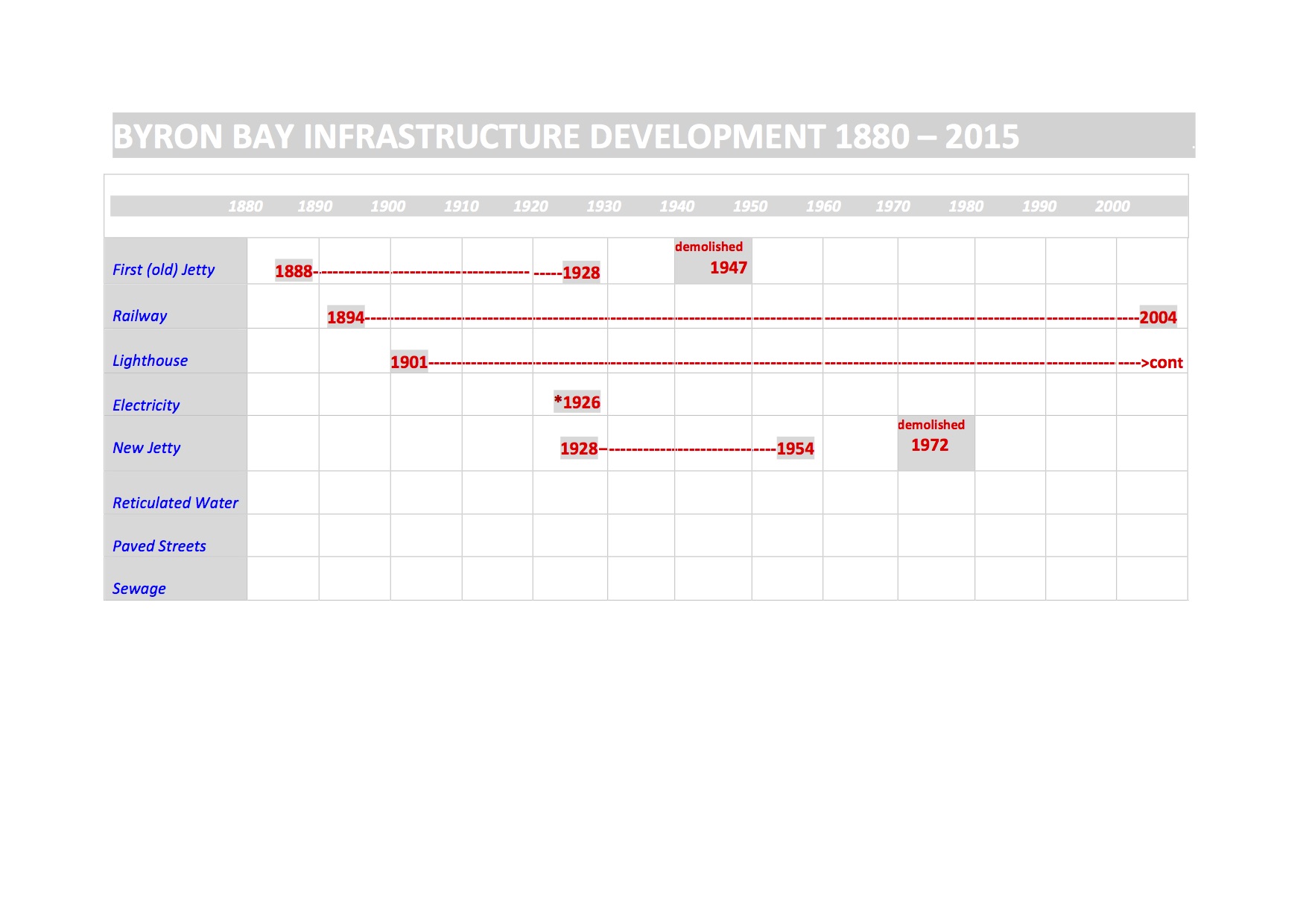

Based on a 1883 marine survey report praising Byron Bay as a safe anchorage for ships it was proposed to build a deep artificial sea port protected by a five metre high break-wall extending from Cape Byron to Julian Rocks and a similar one extending from Belongil Creek toward Julian Rocks. Estimated costs were $500,000. Instead $16,000 was made available to build a timber jetty. Construction started in 1886 and was completed in mid-1888. It extended about 300 metres into the sea from the end of Jonson Street. Unfortunately even the small ships of those times could only come alongside in calm conditions. Cedar logs were the main items loaded initially but often these had to be pushed off the end of the jetty and winched to the ships waiting in deeper water nearby. Soon dairy products, meat and bananas freight had become significant cargo and Byron Bay became a very busy freight port. Horses and then a small railway engine pulled the cargo wagons and passenger carriages along the jetty to and from the ships. By the mid 1890’s Byron Bay had also become the principal passenger port on the north coast. It remained the second busiest port on the NSW coast, excluding Sydney, until the early 1920’s.

(Source EJW – RTRL)

This jetty was lengthened 50 metres and widened in 1910 but required significant ongoing maintenance. Even so it had become too small and dangerous to accommodate the increasingly larger ships. It was replaced by a “New Jetty” in 1928 and became known as the “Old Jetty”. It continued to be used as a platform to fish from, but by 1947 it had become too dangerous even for fishing, so it was demolished.

Jetty (Source – EJW – RTRL)

Sunrise over the old jetty late 1930’s (Source – EJW – RTRL)

BYRON BAY RAILWAY

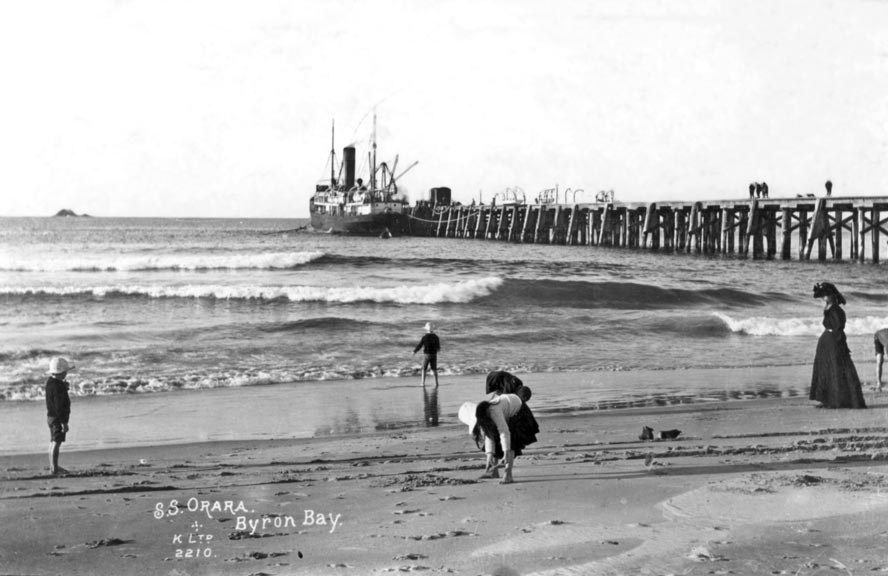

The last scheduled train servicing Byron Bay departed on 16 April, 2004 almost 110 years after the first one arrived. Construction of the Lismore to Murwillumbah railway line; formally the Tweed section of the NSW Coastal Line but also called “the line from nowhere to nowhere” and ultimately the “North Coast Mail Line”; commenced in 1891. The section from Lismore through Byron Bay to Mullumbimby was opened on 14 May 1894. The final section to Murwillumbah was completed in December 1894. Extensions were subsequently opened to Casino in October 1903, and to Grafton in November 1905, but it was not until 1932 that the Grafton to Tweed line was linked to the rest of the NSW state and the national railway network.

A little over 54 kilometres of line with eight tunnels and 105 bridges cut through the shire with 13 stations and sidings. It was linked to the Byron Bay jetties by private rail. Although most stations were closed in the 1970s, and their sites later cleared, Byron Bay and Mullumbimby stations operated until the line closed.

Passengers leaving the Byron Bay station 1910’s (Source – EJW – RTRL)

Initially passenger and freight trains were hauled by steam locomotives which invariably meant soot covered skin, clothing and luggage. These engines were replaced by diesel-electric engines in the 1960’s and 1970’s. As freight volumes diminished in the 1960’s the motor rail and then in 1990 the XPT became the principal trains on the line.

The opening of the railway had a profound effect on settlement within Byron Shire. It catalysed the growth of Byron Bay from a small seaside village to an industrial town and port. From 1894 until the early 1950’s, Byron Bay flourished as a railway and shipping centre with four regular trains bringing goods and passengers to Byron Bay each day as well as special excursion services to the town on weekends and holidays. But with improved roads, more cars and trucks, the destructions of the jetties and closure of the Byron Bay port the railway was utilised less, became uneconomic and eventually unsustainable. Fewer than 40 passengers per day used the service to or from Byron Bay or Mullumbimby in its last days. The tracks have lain idle for more than 10 years but there are proposals to resurrect the line as a rail trail and or a light rail passenger route in the future.

The early settlers fought hard for the line to be built as it was the only effective way to transport passengers to and from ships at Byron Bay port and destinations elsewhere in Australia. It was the critical link along which livestock, supplies and the diverse produce (timber, butter, bananas, bacon, sugar cane, fruit and vegetables minerals) from Byron Bay town and hinterland could be moved to markets.

Byron Bay railway station – 1930’s (Source – EJW – RTRL)

It ferried school children from Byron Bay and other small towns to Lismore or Mullumbimby high schools. It brought inland residents to the beaches of Byron Bay on weekend excursions. Most importantly it carried “the mail” – providing a connection with family, friends and the rest of the world, and it provided employment for many people.

Byron Bay was one of the few stations on the line with a “railway refreshment room” where passengers could purchase meat pies, white bread ham, cheese, tomato or egg sandwiches, small cakes and cups of hot, milky tea, all served on thick, white, indestructible “Railway” crockery. This food had to be consumed quickly before the train departed. Some passengers preferred beer and spirits from the nearby Railway Friendly Bar or “Rails” as it became known to make the journey more comfortable.

Captain Cook Bicentenary Special Train (Source – EJW -RTRL)

Water tower for steam engines after decades of neglect. (Source – EJW – RTRL)

CAPE BYRON LIGHTHOUSE

Showing concrete structure of the lighthouse (Source – EJW – RTRL)

Cape Byron views (Source – EJW – RTRL)

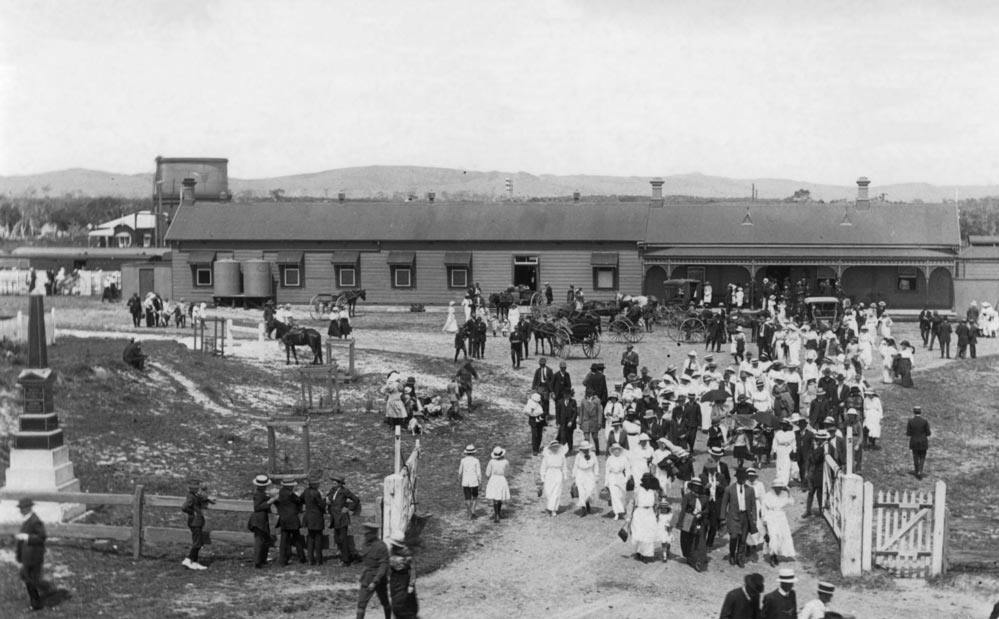

With more than 17 ships wrecked close to Cape Byron, increasing north-south shipping along the east coast of Australia and the growing importance of Byron Bay as a deep-water regional port a commitment was made in 1898 to build a lighthouse on Cape Byron. It was opened on 1 December 1901 with the first light shining that evening as a key navigational aid marking the easternmost point of the Australian continent (28o 38’ 31”S, 153o 38’ 18”E).

Made of concrete blocks fabricated on site from sand and aggregate collected nearby and cement hauled from a barge landing site on Wategos Beach it stands 22 metres high. The four and a half tonne lens, winding machinery, trachyte blocks for the upper deck, 350 kilograms of mercury and other major items were also hauled from Wategos Beach to the site by bullocks.

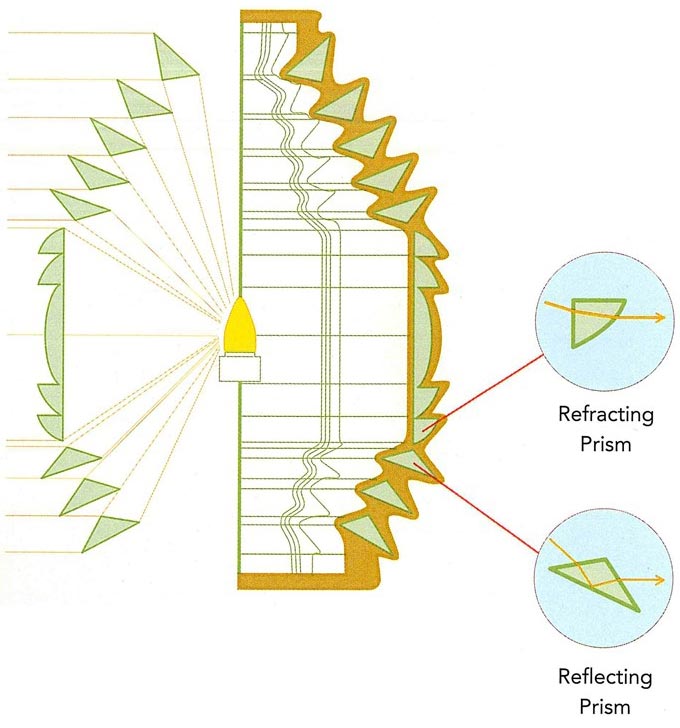

The 2.2 million candela (candle-power) light is the brightest of all lighthouses on the Australian coastline and is visible from 40 kilometres away. Initially the light was generated by burning kerosene on six wicks (145,000 candela). In 1914 this was changed to burning vaporised kerosene on a single mantle (545,000 candela), then on triple mantles in 1922 (1 million candela) and then to an electrically powered 2250 watt bulb in 1959 (3 million candela). The light was converted to an LED source in 2015 from the 1000 watt halogen globe installed in 1976. The light is beamed through a Fresnel bi-valve lens designed and manufactured in France. It is comprised of an inner glass bullseye lens surrounded by rings of refracting and reflecting triangular lead glass prisms. The lens floats in a circular trough of mercury for stability and ease of rotation. Originally the mechanical turning mechanism needed to be wound up many times each night but now electric motors power the rotation.

Inside the Lighthouse (Source – EJW – RTRL)

Fresnal lens showing central bullseyes, inner refracting and outer reflecting prisms. (Source – Webres)

As for all lighthouses the flash sequence of the Byron Bay lighthouse is unique. It flashes for 0.3 seconds every 15 seconds, every night of the year, but the flash sequence has changed four times since 1901, the last in September 1985. The light still shines every night less as a navigational aid in this age of GPS and more as an iconic link to the past.

A red light also shines from the lighthouse in a narrow arc over Julian Rocks. If you can see the red beam you are either about to hit those rocks or are on them.

Three lighthouse keepers were initially employed to maintain and operate the light completing four hour shifts each night. They lived in three cottages on the site from 1901, were reduced to two in 1959 and to one in 1983. The last keeper departed in 1989 after the operation was automated and computerised in 1986. It has been unmanned since.

Lighthouse circa 1920 (Source – EJW – RTRL)

Their well-kept cottages can be rented out but as you relax and enjoy the views and peacefulness spare a thought for the original keepers as they spent all night, every night winding the mechanism, keeping the kerosene lamp going and the lens clean. Etched into the glass windows in the entrance doors to the lighthouse are the words “Olim pericullum nunc salus” which translates from the Latin as “Once dangerous now safe”. Indeed the Cape Byron lighthouse has kept many mariners safe and guided them safely past this craggy cape.

The site is now under the responsibility of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and falls inside the Cape Byron Headland Reserve which is managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service of New South Wales and the Arakwal Aboriginals.

THE NEW JETTY

The wreck of the Wollongbar highlighted the inadequacy of the “Old Jetty” to accommodate the increasing number and larger size of ships using the Byron Bay port after WWI. A larger and longer jetty extending into deeper water was required to provide service to the 8000 farmers, the many agricultural processing industries, and the 80,000 residents of the Byron Bay hinterland as well as to ensure the safety of the many ships and passengers using Byron Bay as a transport hub. Construction of the “New Jetty” began in 1926, was completed in 1928 and cost $114,000.

The “New Jetty” was located well to the west of town extending 650 metres out to sea from Belongil Beach between Don and Manfred Streets. Freight and passengers were hauled to the ships from the main railway line by the “Green Frog” locomotive along two rail tacks extending along the jetty. The last 125 metres were wide enough to accommodate two large travelling cranes used to load ships on both sides of the jetty. These cranes were also used to lift the fishing boats based in Byron Bay from the sea to safety on the jetty when big storms threatened.

The Old and New Jetties Viewed from Cape Byron – 1930’s. (Source – EJW – RTRL)

By the early 1950’s the economics of shipping from the port of Byron Bay had become marginal. The Wollongbar II, the principal freighter of the Northern Steamship Navigation Company sunk by a Japanese submarine in 1943 and other ships commandeered during the war were not replaced. Competition from the railway for freight and passengers and the speed and convenience of road travel further compromised shipping from Byron Bay.

In February 1954 huge waves generated by a severe cyclone destroyed almost 200 meters of the jetty as well as the two large cranes and 22 local fishing boats that had been lifted from of the sea and secured on the widened part of the jetty. This damaged section was not repaired, the cranes were not replaced and the “New Jetty” could no longer fill the role it was built for. Thus ended Byron Bay’s 66 years as a port. The Northern Steamship Navigation Company collapsed financially that year, went into administration and was wound up.

The New Jetty – 1960’s. (Source – EJW – RTRL)

When whaling began in 1954 the end of the “New Jetty” was modified so that whales could be hauled from the sea up on to its deck and transported to the nearby processing works. Whaling ceased in 1962 and after further storm damage in 1963 the “New Jetty” was closed. Being closed did not deter keen local fishermen and women. The large sharks caught from it are legend. The jetty was demolished in 1972 with all traces removed by 1989.