Industry

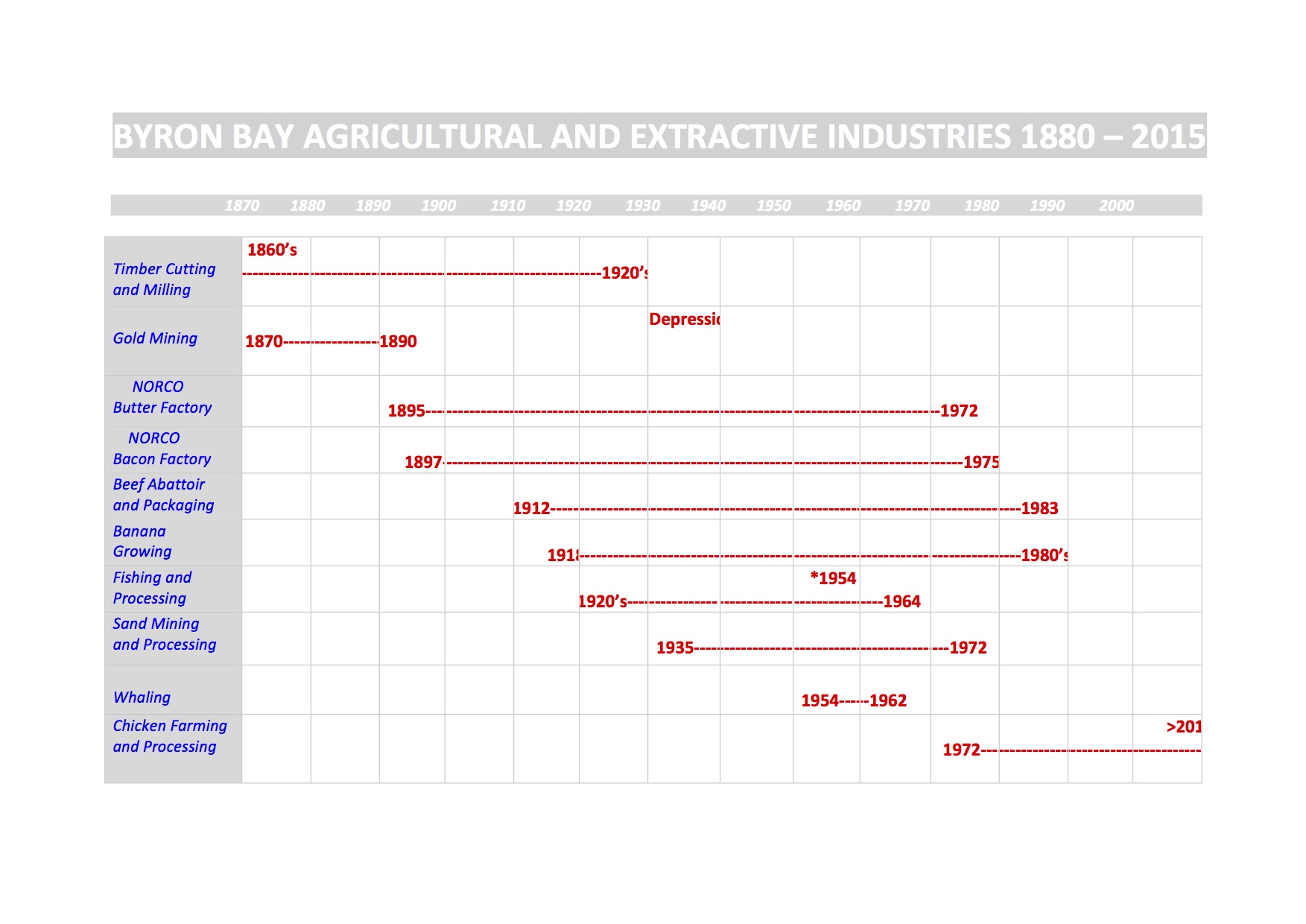

BYRON BAY AGRICULTURAL AND EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES 1880 – 2015

GOLD MINING IN BYRON BAY:

In March 1870, prospector John Sinclair recovered nearly twelve ounces of gold in two weeks from the beaches at the mouth of the Richmond River at Ballina. News of his “ounce per day” discovery soon spread and by September of that year gold had been found on Seven Mile and Tallow Beaches, the two beaches south of the Cape Byron lighthouse, as well as on Main Beach east of the lighthouse. Soon after the discovery the entire coastal strip, except for a reserve between Tallow Creek and Belongil Creek was pronounced a goldfield and open to gold mining.

The gold occurred as very small, free grains within the black sand strandlines on the active beach and in old strandlines and black sand “leads” buried by the dunes behind the beach.

The “black-sanders” usually working in groups of three skimmed black sand from the beach or DUG it from the “leads” until enough was stock-piled to start gold recovery. One then shovelled the black sand into a hopper, one pumped water to wash the sand over mercury-coated copper plates and down a sluice box, and one removed the processed black sand “tailings”. It was hard, monotonous, unrelenting, physical work.

Sluicing black sand to recover gold at Seven Mile Beach – 1935. Morley Photo

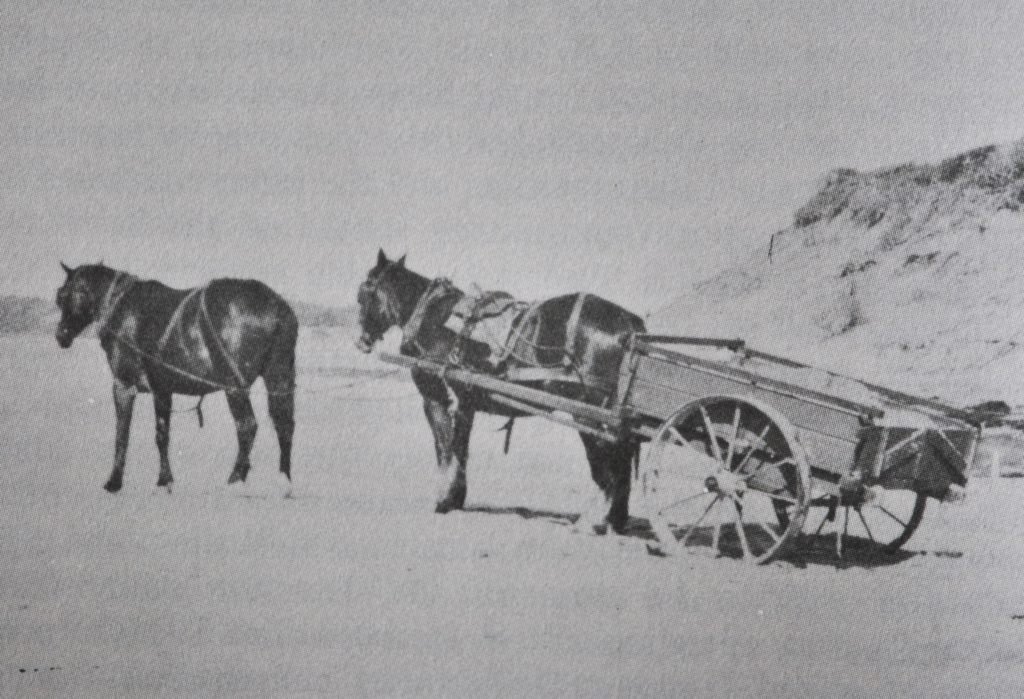

Horses carrying black sand for sluicing on Seven Mile Beach – mid 1930’s. Morley Photo.

The fine gold amalgamated with the mercury on the copper plates to form “amalgam” a putty-like alloy which could be scraped from the copper plates easily. This was the most effective way to recover this fine gold. In primitive operations like these the “amalgam” would be placed in a hollow made in a pumpkin or potato, which was then placed on a shovel and roasted in a hot fire. The fire vaporised the mercury which then condensed in the charcoaled outer layers of the burnt vegetable. This was later crushed and panned to recover the droplets of mercury for re-use. The gold would remain on the shovel as grains or more rarely as a “button” if the fire had been hot enough to melt gold.

By 1890 the richer deposits had been worked out and only a few prospectors and miners remained seeking their fortune.

This gold-field was known as the “poor man’s diggings” as everybody found some gold but no one made a fortune. No mechanised operations run by large companies were developed. The average yield for each miner was between a half and one ounce of gold per week. Total estimated production from Byron’s beaches is 20-30,000 ounces. In difficult economic times such as the depression years of the early 1930’s the unemployed and desperate returned to these beaches to eke out a meagre living.

Unknown to these gold miners the black sand they discarded contained a fortune in other minerals. But it was not until 1935 that production of rutile and zircon from these beaches began.

Fine beach gold – recovered after retorting. Main Photo.

Black sand “lead” from Seven Mile Beach. Main Photo

AGRICULTURE:

Notwithstanding the opportunity to select free blocks in the Byron Bay area from 1862 it was not until 1881 that the first four were chosen. This late selection reflects the fact that behind the thin coastal strip of swamps and dunes the land rose quickly to hills covered in thick bush and forest. This was known as the “Big Scrub” and was difficult to access and to clear compared with the rich flat alluvial soil along the banks of the major rivers to the north and south. The first settlers chose a “Big Scrub” block, usually of 640 acres, to clear and to farm.

Early settlers tent (Source – EJW – RTRL)

The first commercial crop grown was sugar cane with small sugar mills built at Nashua in 1885 and Ewingsdale in 1887. But by 1890 both had closed as the farmers switched to more profitable dairy farming. Remaining cane farmers sent their cane to the big CSR mill at Condon on the Tweed River.

Jersey cows – the basis of the Byron Bay butter industry EJW photo RTRL

Delivering milk to the NORCO milk factory 1900’s EJW photo RTRL

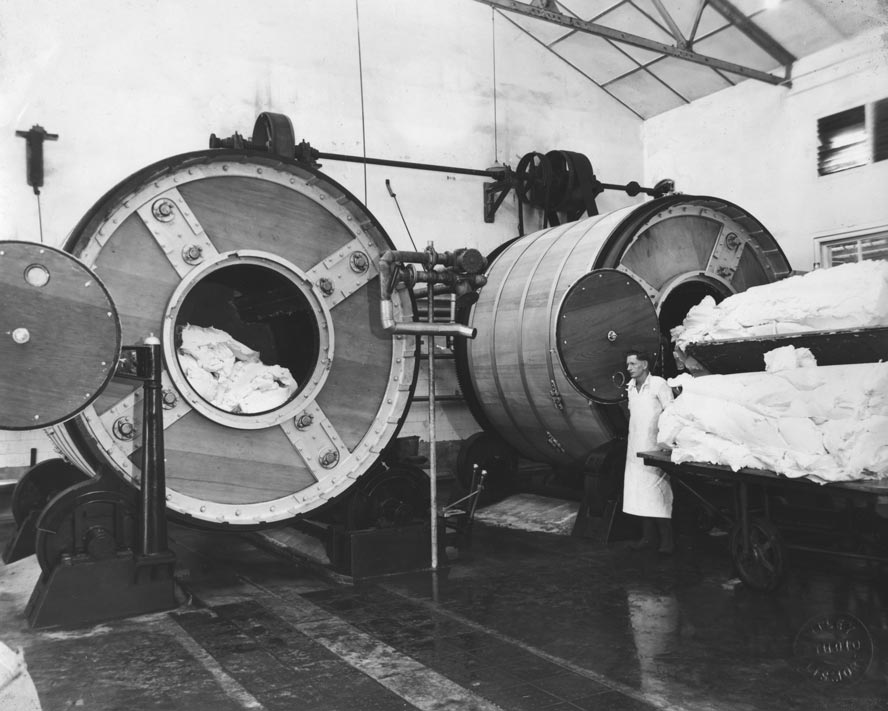

Dairy farming expanded significantly in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s driven by the development of centrifugal separators that allowed cream to be separated from milk and by the development of refrigeration which allowed the products to be transported. In 1895 the production from the Byron Bay area and hinterland underpinned the establishment of the NORCO Byron Bay butter factory which was built at the southern end of Jonson Street, Byron Bay. Milk production grew rapidly and was converted to butter and small amounts of other dairy products to be exported from the Byron Bay port to Sydney and ultimately to global markets. By the 1920’s 25% of NSW’s milk production was processed at Byron Bay and by the mid 1930’s Byron Bay was producing 35,000 tonnes of butter annually or 60% of NSW’s total. NORCO came to dominate the dairy industry and took over smaller factories established in the shire at Eureka (1890), Binna Burra (1912) and Mullumbimby (1937).

Norco butter factory south end of Jonson Street – 1930’s EJW photo RTRL

A few years after the dairy factory was built a piggery was established in Byron Bay with the animals fed the skim milk and lesser whey by-products. This was the basis for a large bacon, ham, sausages and small goods industry also part of NORCO’s Byron Bay business.

Bacon sides and hams hanging in the smoking room – 1950s EJW photo RTRL

Large butter churns – 1950s EJW photo RTRL

For nearly 80 years NORCO was the biggest employer in town and the largest contributor to the town’s economy. However, by 1972 milk intake had fallen more than 30% from a peak intake of 790 million litres of milk in 1934. Dairy farmers were squeezed by falling butter prices, increased operating costs and a need to inject more capital into their operations to meet bulk milk collection requirements and increased health and cleanliness standards. More and more farmers changed to beef farming, horticulture or simply sold their land as lifestyle blocks. Production at NORCO’s Byron Bay butter factory ceased in 1972 and its bacon factory closed in 1975. After closure parts of the factories were demolished. The remaining structures together with new buildings are now occupied by the Services Club, Mitre 10 hardware, plus Repco and Singh’s motorcar supplies and services.

Not all land in the shire was dedicated to dairy farming. Bananas and pineapples were successful and significant crops in the early years following initial settlement. Bananas became very important following WWI with annual production growing quickly to more than 200,000 cases and 13% of the state’s total production in 1941. Production peaked in the mid – 1960’s and fell to 1930 levels in the mid-1980’s.

Beef production was also an important component of Byron Bay’s agricultural history with a beef processing meatworks established just before WWI. Variable economics saw production start and stop several times before the meatworks was acquired by Anderson’s in 1930. With an increased and reliable cattle supply, modern machinery and expanded capacity it became a significant beef producer in the early 1930’s, exporting to Sydney markets and to Britain. From 1959 boneless beef was exported to the US market. Beef production peaked in 1964 and declined steadily until 1983 when the meatworks was closed.

With the closure of the meatworks Byron Bay’s 90 year “butter-bacon-bananas-beef” agricultural era from 1895-1984 was over.

Macadamia nuts, coffee and other speciality fruits are the main agriculture products now.

BYRON BAY MEATWORKS

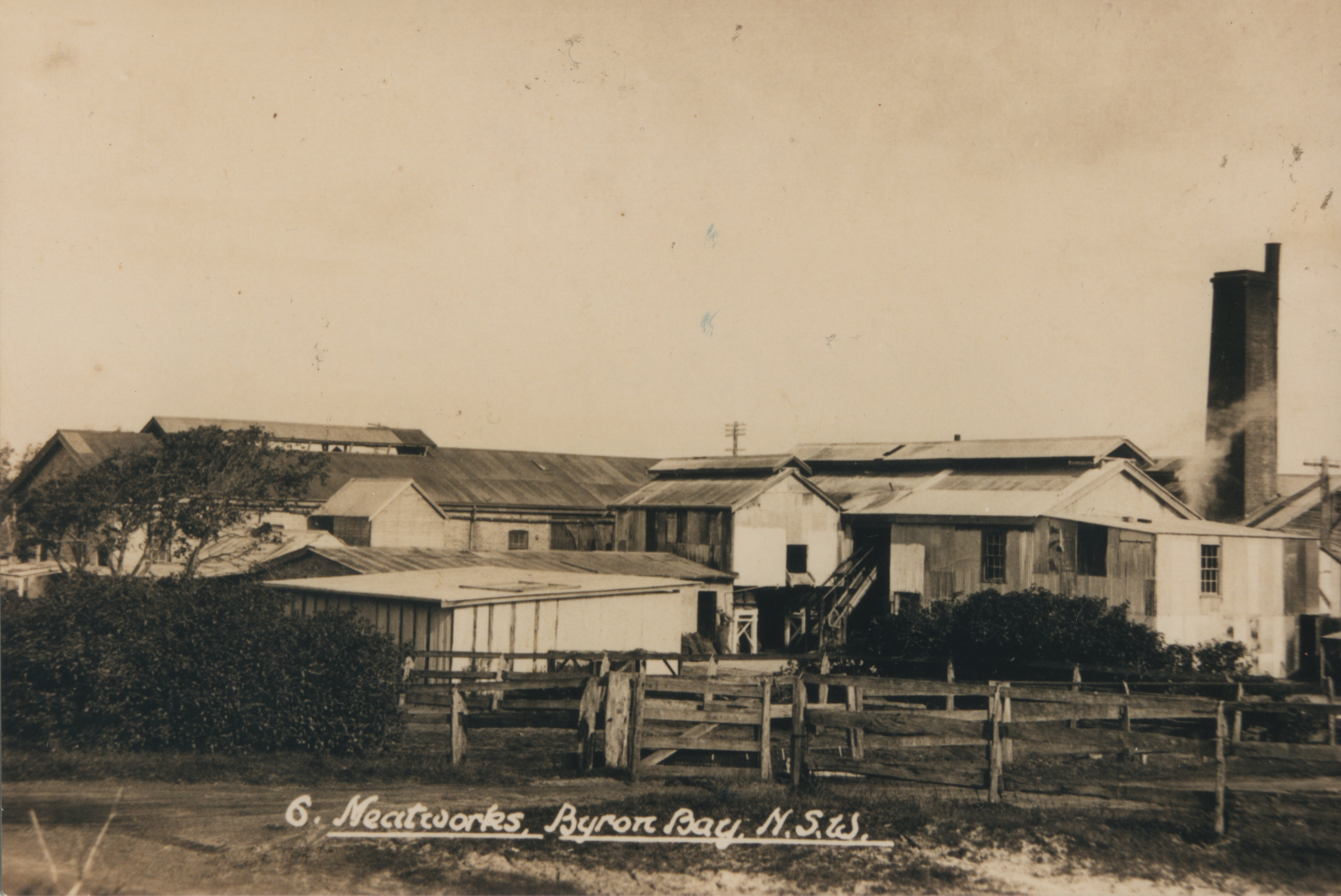

In 1912 Byron Bay was chosen as the site for the Byron Bay Co-Operative Canning and Freezing works because of its port facilities. Northern Rivers farmers formed a Co-Operative as an outlet for their surplus stock as at that time livestock had to be forwarded to Sydney for slaughter. However by 1915, the company was running at a loss and in 1916 the Company was leased to Reynolds and Son of Sydney and Melbourne. The later years of WWI guaranteed a market for its product and by early 1919 the works employed 100 people and 80 to 100 head of stock were killed daily. The buoyancy did not last and in late 1919 the works closed down.

Byron Bay Meatworks – 1930’s EJW Photo – RTRL.

In 1924, A W Anderson, founder of the Anderson chain of butcher shops and meat companies, together with A J Thompson purchased the lease and assets of the Byron Bay Meatworks. However in 1927 their lease expired. A W Anderson reopened the works in 1930. He installed new machinery, more refrigeration and a large storage freezer and promoted the plant widely to attract livestock for processing to supply the Sydney wholesale beef markets.

Its reopening was seen as a vote of confidence in Byron Bay in the dark days of the Depression. Anderson was a dynamic businessman who understood perfectly the meat industry as well as the economics of marketing and advertising. Anderson opened his first retail shop in 1918 in Sydney specialising in sausages. Endowed with a natural news sense and keen appreciation of the public relations value of humour as well as a flair for advertising well in advance of his time he advertised he would place a sovereign in a special lot of sausages in his Sydney shop and the shop was rushed. Anderson’s sausages received free publicity and also further publicity was generated when he appeared in court on a traffic obstruction charge.

The previous owners had not been able to ensure that stock was maintained and he embarked on a vigorous campaign with daily advertising in the Northern Star and other newspapers.

In early 1933, a fertilizer department was added to the site and the following year the plant was considerably expanded with the addition of more cold store rooms and other improvements to enable the company to enter the overseas trade. 1934 saw the commencement of exports to Britain under the brand name BYROND.

A new era commenced in 1959 with the market for boneless beef, prepared to exacting standards and specifications, exported to the American market.

Meatworks site and new jetty in 1966 with waste “slick” drifting eastwards. NSW Govt Image

Anderson Meat Packing commenced an extensive rebuilding programme of the abattoir and packing plant worth over half a million dollars in 1964. 1965 and 1966 were the boom years for the company and the local economy – payments to farmers for their livestock, wages and salaries to the employees, as well as transport companies. The heavily mechanised and extensive refrigeration plants using locally generated electricity also added to local revenue.

Meatworks in 1983 the year it closed. EJW Photo – RTRL.

Meatworks in 1972. EJW Photo – RTRL.

In 1968, Andersons sold the company to FJ Walker who in turn in 1983 sold to Elders IXL. The Meatworks had been operating at a loss for some time and in October 1983 closed with the loss of 360 jobs, causing genuine hardship for the employees with few employment alternatives.

The Meatworks site and holding grounds have now been rehabilitated and are the location of private dwellings and tourist accommodation and restaurants.

MINERAL SAND MINING:

The gold miners who came to the Byron Bay area in 1870 and for the next two decades mined alluvial gold off the beaches extracted it from the heavy black sand and cursed this sand for filling their sluice boxes and making it extremely difficult to capture the fine gold. They threw it away in disgust little realising that within 40 years it would become very valuable indeed.

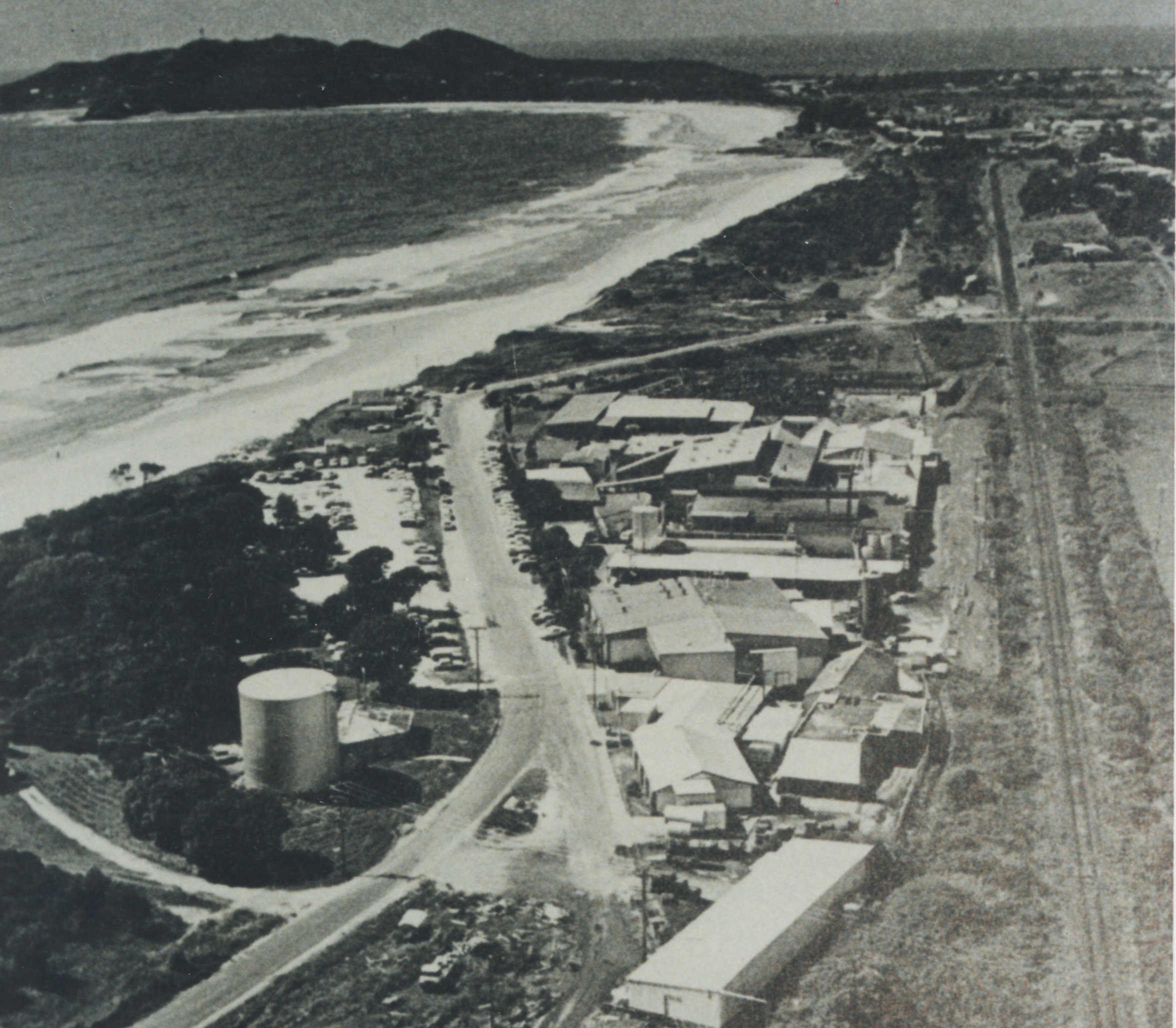

In 1934 the company Zircon Rutile Limited (ZRL), was formed in Byron Bay. It started sand mining in January 1935 at Seven Mile Beach south of Tallow Beach, and transported the black sand concentrates to its treatment plant on Jonson Street in Byron Bay (now Woolworths’ Supermarket site). In April 1935 it became the first company in the Australia to separate a clean, high-grade zircon product from the black sand. In 1943 it became the first company in the world to produce separate, high-grade rutile, zircon and ilmenite concentrates from black mineral sands. These were bagged and exported from Byron Bay to the world. The zircon was used in the foundry, ceramic and enamel industries. From rutile and ilmenite “titanium white”, used as pigment in paint and plastics, and titanium metal were derived. To conserve capital ZRL initially used “black-sanders” to scrape, dig, concentrate and stockpile the black sand from the beaches and “leads” in the dunes to be collected by company trucks. These men were paid $4.80 for a 44 hour week, lived in tents near the beach, used the sea to wash and relax in and as a source of fresh food. They kept any gold, platinum and tin they found.

By the end of World War II ZRL was mining in its own right and was the major supplier of rutile and zircon; all from Seven Mile Beach. In 1947 it expanded north to Tallow Beach, starting at Broken Head at the southern end then moved to Taylor Lakes, Suffolk Park, Tallow Creek and finally closer to Cosy Corner beneath the lighthouse.

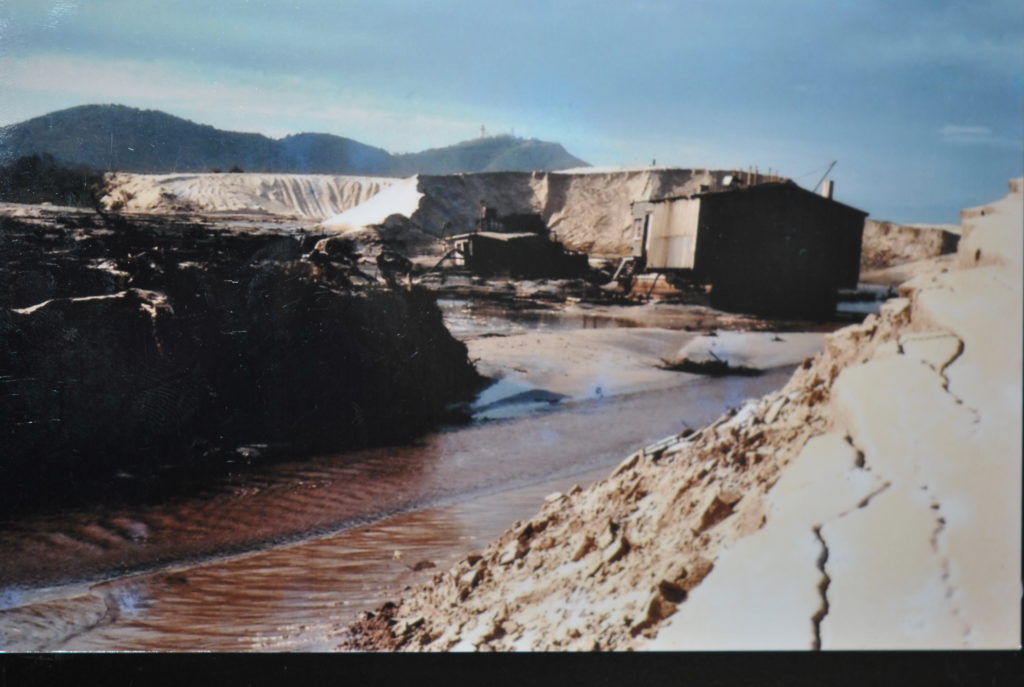

In 1948 floating suction dredges replaced most of ZRL’s bulldozers, scrapers and trucks. Banks of spiral concentrators on these dredges separated the heavy minerals simply and cheaply from the other sand grains. Heavy mineral concentrates were pumped to the treatment plant which now operated continuously. The remaining sand was pumped back to the mined areas and in 1951 ZRL became one of the first companies to rehabilitate mined areas when it began reforming and replanting the dunes, unfortunately not with native plant species but with imported plants such as “bitou bush” which later infested many areas.

From 1950 to 1961 ZRL was the largest and most profitable producer of zircon and rutile in Australia and the world with Seven Mile and Tallow Beaches its mining focus and Byron Bay its prime treatment centre. However, in November 1961 ZRL ceased to exist; taken over by AMC. AMC and others continued mining at Tallow Beach, then moved inland, and finally to the beach and dunes at Main Beach.

Sand Mining on Main Beach in 1967. EJW Photo – RTRL.

Dredge sand mining Tallow Beach early 1960’s – Lighthouse in background. EJW Photo – RTRL

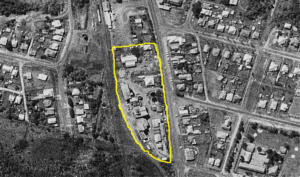

Sand mining ceased in Byron in 1972 driven by opposition from conservation groups as much as availability of resources and industry economics. Processing continued until 1974 and the plant was demolished and the site cleared by 1977. Some mined areas are now incorporated in Arakwal National Park; some are public places or infrastructure and some contain private houses, commercial and other buildings. Until the mid-1960’s there was no foreshore park, no walkway, no Lawson Street and no buildings between Middleton to Massinger Streets in Byron Bay. Dunes and swamp extended inland as far as Marvell Street and the sports fields. After the dunes were mined the land was reformed, developed by government and sold as Sandhills Estate. Private dwellings, tourist accommodation, restaurants, and community structures as well as green space are now located on the mined area.

In 39 years of production more than half a million tonnes of premium mineral sand products worth more than $500 million at current prices were mined from Byron’s beaches and dunes for export to the world. Byron Bay played a pioneering, innovative and wealth-creating role in this industry.

Much concern accompanied the disposal of “radioactive waste” from the processing plant. This radioactivity was caused by monazite, a thorium-bearing, resistive, heavy mineral contained in the black sand concentrated from the beaches. In the early years after WWII the Australian Federal Government mandated that this mineral be recovered and stored by the sand miners as thorium was a potential fuel for nuclear power generating stations. Ultimately uranium became the preferred fuel and most mineral sand producers were left to dispose of any monazite they could not sell. Sand miners either mixed it with normal sand and buried it or returned it to the beach whence it came.

ZRL’s mineral processing plant in Jonson St – 1971, now Woolworth’s site. NSW Govt Photo

Red Devil sports ground and High School areas being sand mined – 1966. NSW Govt Photo

Approximate boundaries of main areas mined for mineral sands. Google Image

Area behind Main Beach after sand mining but before development – 1971. NSW Govt Photo

FISHING IN BYRON BAY

The Arakwal Aborigines were harvesting fish, shellfish and sea mammals from the Byron Bay rivers, estuaries and sea for many millennia before European settlers arrived. Using spears, fish traps and nets they made seafood a significant part of their diet. Many large “middens” along the coast containing millions of shells and fish and mammal bones attests to their skilfulness. Carbon dating of these remains attest to a thousand of years of accumulation.

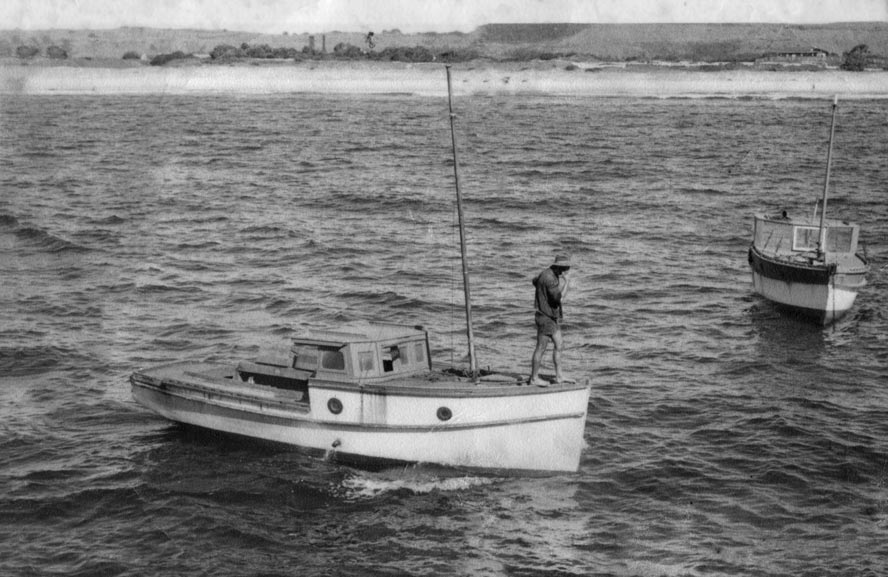

After the “old” jetty was completed in 1888 fishermen in small boats commenced catching fish in the bay; firstly for local sale and later for export to other Australian markets. The first commercial fish processing and canning plant was Poulson’s Fisheries Ltd built in Fletcher Street in the early 1920’s selling “fresh” iced fish, canned and smoked fish. Interestingly Poulson’s largest fishing boat and several other fishing boats were wrecked in the same storm in which the Wollongbar was wrecked.

A large haul of fish on Clark’s Beach -1920’s. EJW Photo – RTRL

During the “mullet run” spotters on high points on Cape Byron would relay the location and path of the northward-migrating schools of fish to the waiting fishermen. These fishermen would run their nets around these huge schools netting many tonnes of fish in a single haul. Fishermen on the beach would row out and circle part of the school and drag their bulging nets up onto the beach often allowing locals to “help themselves” before selling the remainder to the processing plant.

Fishing boats on the old jetty 1919. EJW Photo – RTRL

At the end of WWII the Byron Bay Fisherman’s Cooperative was established with its depot in Lawson Street. New prawning areas, reef fishing spots and schooling sites had been identified and provided a greater variety of catch (bream, tailor, snapper, perch jewfish – all caught on hand lines) and an extended fishing season to underwrite the economics of this local industry.

When the “new” jetty was completed in 1924 a large number of fishing boats supplying the Cooperative used it as a base and to haul their craft from the water for servicing and for protection in severe storms. As a precaution against “the cyclone of February 1954” all of the fishing fleet had been hauled onto the “new” jetty out of harm’s way but this major storm destroyed much of the jetty and 23 of the 32 fishing boats.

The fishing boats were mostly small one man craft. EJW Photo – RTRL

Those left were the smaller craft. The “new” jetty was never repaired and without this access and shelter most of the fleet relocated to the Brunswick River. Their catch was transported to Byron Bay and still processed here until 1964 when the Brunswick Heads facility was built. The last fishing boats left Byron Bay in 1966.

Recreational fishing from beach, jetty and boat and sport fishing have always been an important part of Byron Bay’s fishing history and still are. Many large sharks were caught from the jetties and the beach. Keen amateurs have launched their boats from the ramp at “The Pass” for nearly 100 years ensuring even in the event of not catching fish they have had an adventure; releasing and retrieving their boats through the surf.

Marine habitat and marine species in the waters of Byron Bay are now protected in the Cape Byron Marine Park declared in 2002 and comprising 22,000 hectares. This Park extends 5.6 kilometres seaward from the “mean high tide mark” from Brunswick Heads in the north to Lennox Head 37 km further south. It includes all tidal portions of the Brunswick and Belongil Rivers and Tallow Creek and part of the “overlap zone” where warm currents from the north and cool currents from the south converge to make it one of the most attractive fishing grounds.

WHALING AT BYRON BAY

Whaling commenced in Byron Bay in mid-1954 after the severe cyclone early that year destroyed the new jetty and most of the local fishing fleet. The newly formed Byron Whaling Company was awarded a quota of 120 humpback whales for that year. It took its first whale on 29 July, 1954. Its annual quota remained 120 until 1959 when it was increased to 150. Total number of whales harvested was 1146, producing more than 10,000 tonnes of whale oil. The company focused on taking male whales travelling north during the annual May to August migration from the Antarctica feeding grounds to their Coral Sea birthing and mating areas. This was when they had the largest reserves of blubber for conversion to oil. Whales were leaner on their return journey to Antarctica as they would not have eaten since leaving. Taking females with calves was prohibited.

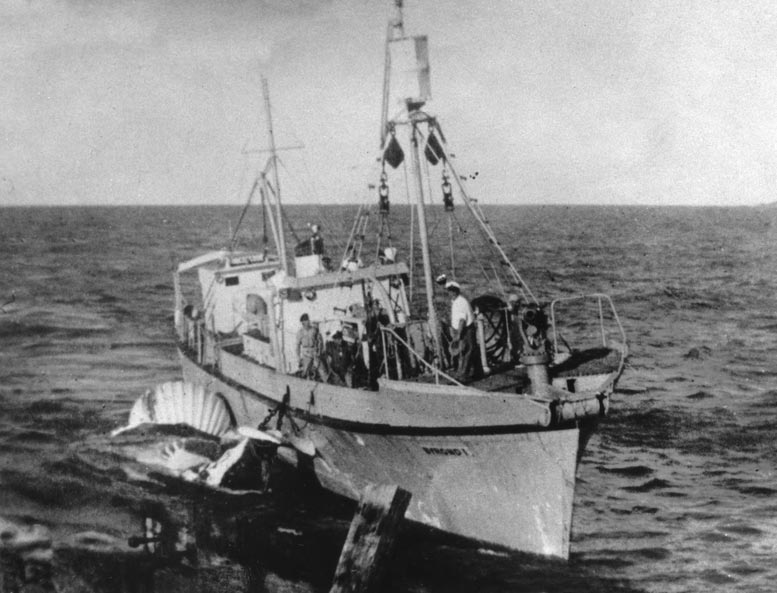

Whaler Byrond 1 bring harpooned whale alongside the new jetty. EJW Photo – RTRL

After spotters sighted the whales the chasers would race to them and get close enough to hit them with the harpoon. After harpooning and killing the whales the carcass was filled with air to stop it sinking and then towed back to the “new” jetty where it was hauled from the water, placed on a flat top rail wagon and hauled to the nearby processing factory.

The Green Frog railway engine hauling a whale to the factory. EJW Photo – RTRL

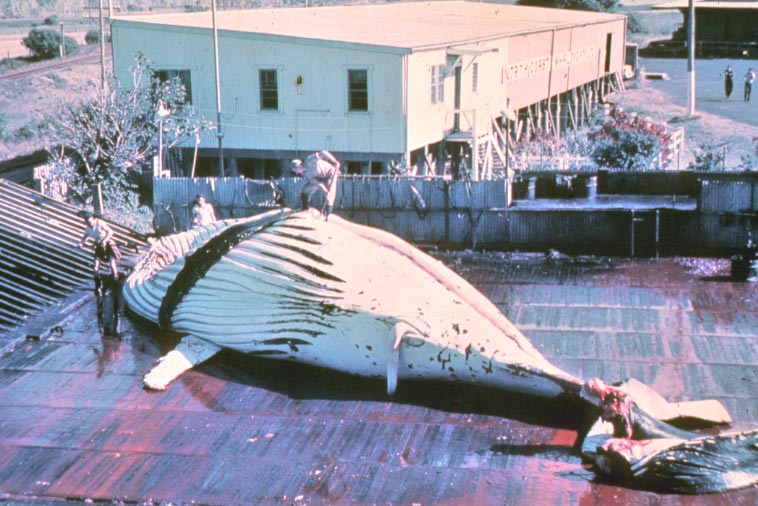

The flensers removed the skin and valuable blubber, then the meat. The skin and blubber were boiled to separate the valuable oil (about 10 tonnes per whale) to be used for making margarine, explosives, cosmetics, lubricants and detergents. The meat was frozen and exported. Bones were sawn into manageable portions, oil was extracted from them then the bones and other solid waste was converted to dry “meal” to be used as animal feed or fertiliser. Liquid waste was pumped to sea through a “blood pipe” thus accounting for the many large sharks in the Bay.

Flensers commence “opening” a male whale. EJW Photo – RTRL

Some whales were hauled up the beach to the factory. EJW Photo – RTRL

Peeling back the skin and blubber. EJW Photo – RTRL

In its first year the company had little trouble filling its quota with large whales accessible close to Cape Byron. On “good” days the whalers Byrond 1 and Byrond 2 would bring three or four whales to the plant. But as each season went by hunting became increasingly difficult. The whalers spent more days at sea, sailing further away from Cape Byron to locate their prey and found the whales were smaller and leaner each year. In 1962 only 107 whales were captured in 144 days of hunting for a yield of 5.9 tonnes of oil each compared to 150 whales captured in 56 days to yield 9.7 tonnes of oil each in 1959. This was unsustainable economically and ecologically and the Byron Whaling Company ceased operations in October 1962.

At that time it was estimated fewer than 5,000 humpback whales remained in the southern oceans. By 1966 massive overfishing, allegedly by Soviet whaling fleets, in the Southern Ocean meant both the Australian and New Zealand humpback whale populations were essentially extinct. The whaling industry collapsed. The humpback whale population is now recovering with 35,000 expected to pass Cape Byron on their annual migrations.

Chicken Processing

Sunnybrand Chicken started in the early 1970s as a chicken processing plant employing 3 people handling 200 chickens per day. It quickly grew into one of Byron Bay(Cavanbah)’s largest industries employing upwards of 400 people capable of processing 300,000 chickens per week and had an annual turnover of $100m.

After 30 years as a locally owned and managedoperation, it was sold to a major Australian chicken processor before being on sold to an American company who closed the operation in 2016.

This marked the end of Byron Bay(Cavanbah)’s industrial era

KINGS OF THE SEA

There once was a time when life was sublime and whales were the Kings of the sea;

They travelled our shores aloof from the world and roaming majestic and free.

Then man came along and shattered their song with the thunder of guns in their ear;

We woke to that roar but chose to ignore the whales lying dead on the pier.

And meanwhile at school they pointed with pride at all of the progress we’d made,

By processing meat and premium oil, we’d boosted our external trade.

And papers proclaimed –‘An industry born.’ Our clippings recorded the news.

And folk far and wide seemed quite satisfied, expressing no alternate views.

There wasn’t a thought of rights or the wrongs, when cannons heard clearly by all,

Were merely a signal to climb a sand hill, to witness the hunt and the fall.

While back on the pier the bloated remains were toted like trophies of war;

Towed slow on a track that wound its way back to crowds standing blankly in awe;

They came in by bus from north and the south, to bolster the tourist trade;

They held a tight handkerchief over their nose while eating meat pies in the shade.

And down on the floors the butchers’ backs bent for twenty four hours a day.

The stench and the steam hung low in a cloud that billowed out over the bay.

The flensing knives flashed and steam winches strained as blubber came crackling clear

And workers sweat flowed with the blood on the floors from May to October each year.

For eight years straight the chasers would wait for the cream of the crop to come by

And year after year less whales would appear, ‘till hardly a whale came to die.

One-twenty we took in late ‘fifty four.’ They later allowed thirty more

And by sixty two the numbers were few – we dragged the last humpback ashore.

“And earlier years were good!” So they said. “We captured our quotas with ease.”

“It’s culling down south that’s caused their demise, down there they just shoot as they please”.

Yes that’s how it was not so long ago, but now, when the new calves are born;

They find human friends instead of the guns that greeted their parents at dawn.

But peace on our shore is only one door and freedom will need many keys

As homeward they go where cannons still glow, down there, in those dark southern seas.

Col Hadwell, 1998