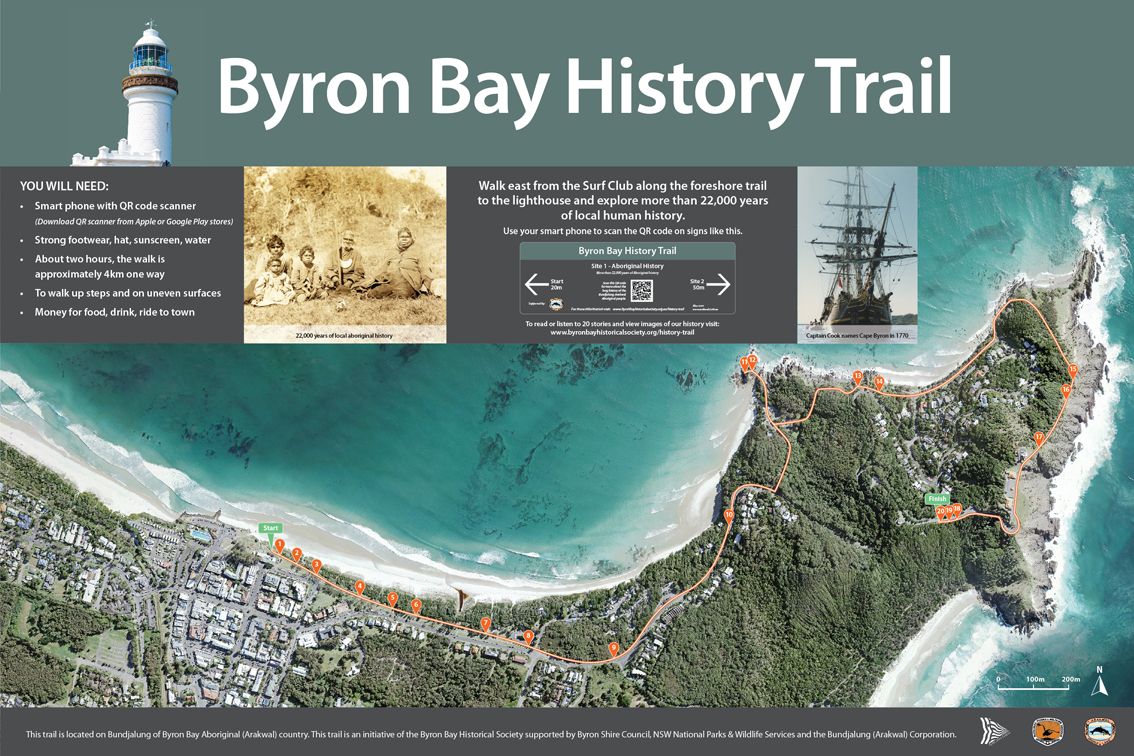

History Trail

Site 1

ARAKWAL HISTORY

The Bundjalung mob of Byron Bay …. The Arakwal /Bumberlin people have lived in the coastal landscape around Byron Bay area for at least 22,000 years

They are one of over 400 Aboriginal tribes that co-habituated Australia before European occupation.

The Arakwal people are recognised as the traditional Aboriginal custodians of the Byron Bay district, Arakwal country over which their native title covers 241 square kilometre it includes the lands and water extending from Brunswick Heads along the Brunswick river to Durrumbul in the north, from Jew Point through to Newyrbar in the south, the Coorabell and Koonyum Ranges in the west and a distance of approximately 100 meters east of the mean high water mark.

A detailed map of Country can be found on the Arakwal website see links below.

The Arakwal people have asked that their stories be told by them direct from their website. The Byron Bay Historical Society respect the Arakwal peoples request and refer and encourage you to their website by clicking on the link below. http://arakwal.com.au/

All other Audio/written/picture stories on this history trail are direct from the Byron Bay History Society website which you are now linked too.

We hope you enjoy your journey into the early history of Byron Bay.

Site 2

EARLY EXPLORERS

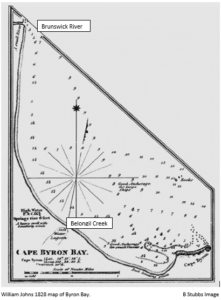

After Captain James Cook “named” Cape Byron(Walgun) on 15 May 1770 many other ships passed by before any white people landed in the area, including Matthew Flinders in 1802 in Investigator and Captain John Oxley in Mermaid in 1823 on his survey of the NSW coast and Moreton Bay.

It was Captain Henry Rous, and William Johns in 1828, in the Rainbow who made the first documented landing. Rous and his crew collected depth soundings of the bay. Johns prepared a map of the coast and bay between Cape Byron and “a small river to the north”, Brunswick River. That map shows a salt water lagoon (Belongil Creek), Julian Rocks(Nguthungulli) and good anchorage at what is now Clarkes Beach just west of “The Pass”(Currenba). They identified the bay as providing safe anchorage for both large and small vessels.

Surveyor Robert Dixon’s visit to Cape Byron in June 1840 is the first documented white person visit by land. He recorded a tribe of fine-looking, Aboriginal men fishing with nets and established a trig station on Cape Byron as a base for future surveying.

With the passing of the Crown Lands Alienation Act in 1861 the land in the Byron(Cavanbah) area was open for free selection by settlers. However, a reserve around Cape Byron extending from Tallow Creek to Belongil Creek precluded selection along this part of the coast. Part of that reserve survives today as the Cape Byron Reserve.

There were still no signs of white habitation at or near Cape Byron in 1865 when the NSW Inspector of Police visited. Rugged terrain, deep rivers and dense vegetation prevented easy access by land from any direction. It is recorded that the cedar-getters were at Byron Bay by 1869 and by the early 1870’s had set up tent camps at Byron Bay.

The earliest dwelling recorded within the present Byron Bay area was a lonely slab hut in Palm Valley first noted in 1882. This was an illegal occupation.

Site 3

EARLY SETTLERS

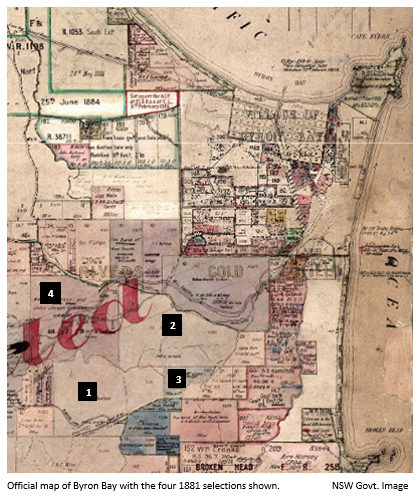

With the passing of the Crown Lands Alienation Act in 1861 land in the Byron Bay area was open for free selection by settlers. However, it was not until 1881 that the very first selection was made. Thomas Skelton selected portion 1 of 640 acres, Parish of Byron, on 2 June that year, followed by Joseph Wright, who selected 100 acres and Eli Hayter who selected 640 acres on 16 June. The final selection for that year was for 604 acres on 7 July by James Glissan. These earliest selections were on the higher land south-west of Cape Byron, well outside of the area that is now the town of Byron Bay.

In 1882 the land rush began and by year end much of the best land was claimed. But the first settlers faced great difficulties clearing land for cropping or grazing. From the trees they felled they built primitive timber slab huts and crude fences all without labour or nearby supplies. Nature did not cede the land easily. Poisonous and biting insects, venomous snakes, toxic plants, fire, flood, disease were the gate-keepers. Great was the hardship for those that fell ill or were injured.

The earliest dwelling within the present Byron Bay area was a timber slab building in Palm Valley built by David Jarman, noted in 1882. It was a hotel and a stopping place for people travelling north and south along the beach “highway”.

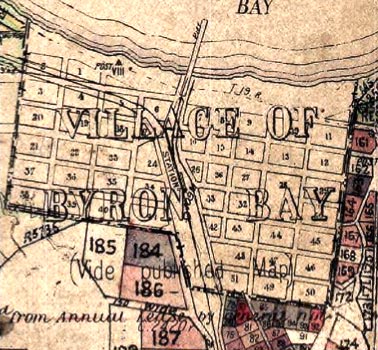

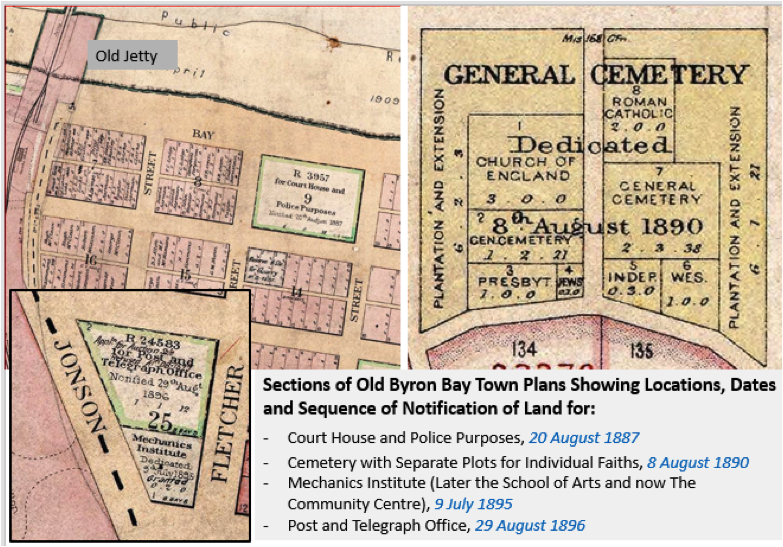

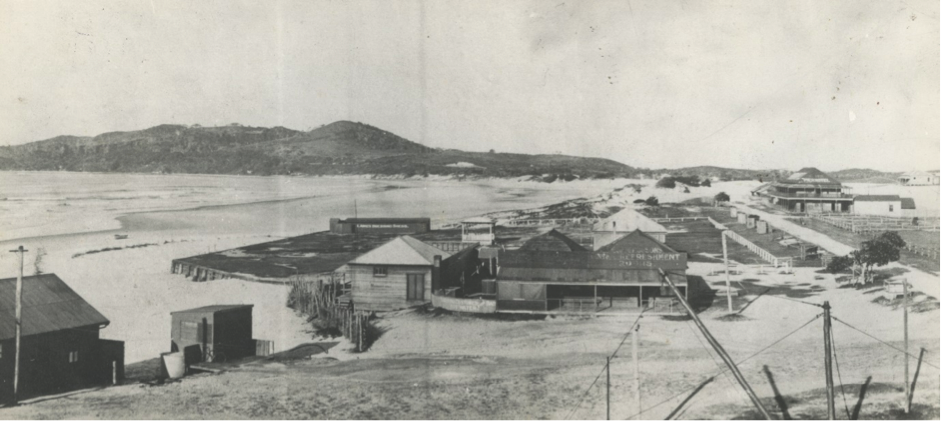

Plan of Byron Bay showing blocks, streets, old jetty, railway line and station. NSW Govt Map.

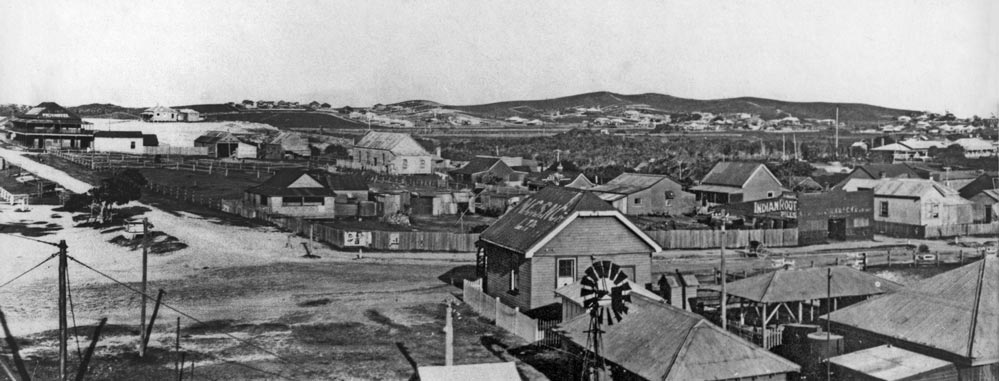

Looking south east from the corner of Bay and Jonson Streets (Source EJW RTRL)

In 1884 the village of Cavanbah was laid out behind Main Beach by surveyor Poate. The village and of the surrounding townlands were gazetted on 19 December 1885. All the 40 half-acre lots offered for sale in July 1886 were purchased including several by David Jarman. Cavanbah was proclaimed a village in 1890. In 1894 Cavanbah was renamed Byron Bay. It was declared a town on 28 August 1896.

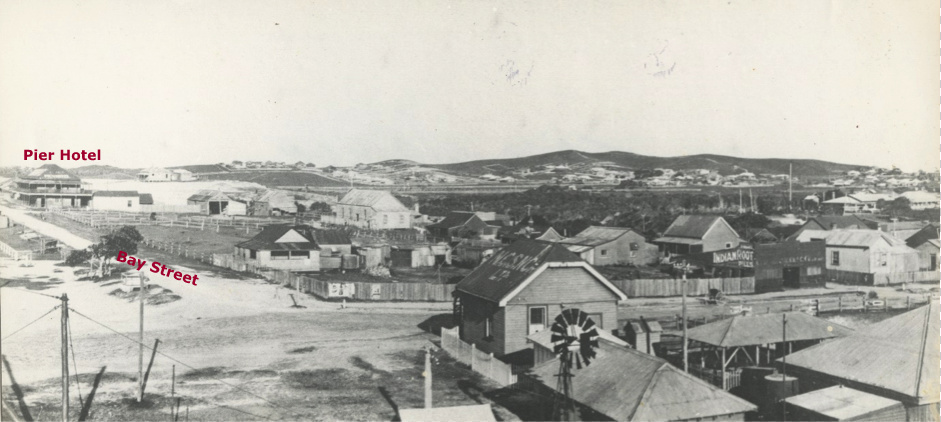

View east across upper Jonson St. Bay St, Pier Hotel on right – early 1920’s. EJW Photo – RTRL

Site 4

EARLY BYRON BAY

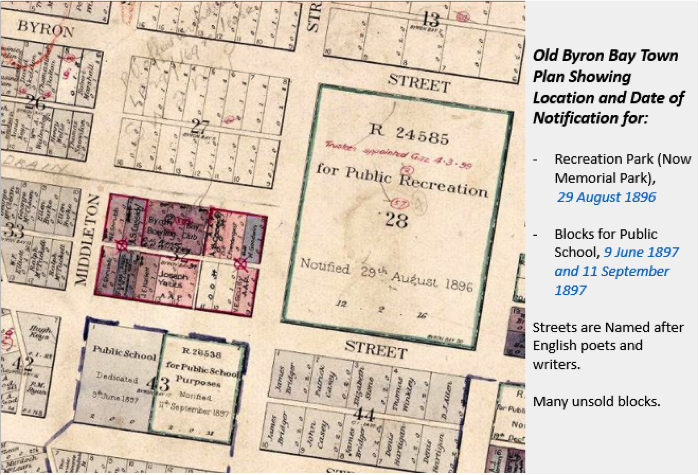

While there is very little written about the growth of Byron Bay town in the decade after the very first quarter acre residential lots were sold in July 1886, old maps show significant planning and development.

Early Byron Bay Town Plan

The first lot dedicated to services was for a courthouse and police purposes in 1887; the second in 1890 was for a cemetery; with specific areas set aside for the dead of each faith. Then followed land dedicated to a community centre in 1895, a post and telegraph office in 1896, a recreational park in 1896 and a public school in 1897. The first church (Anglican) welcomed worshipers in 1898. This sequence presumably reflects the needs and priorities of a pioneer community at the time.

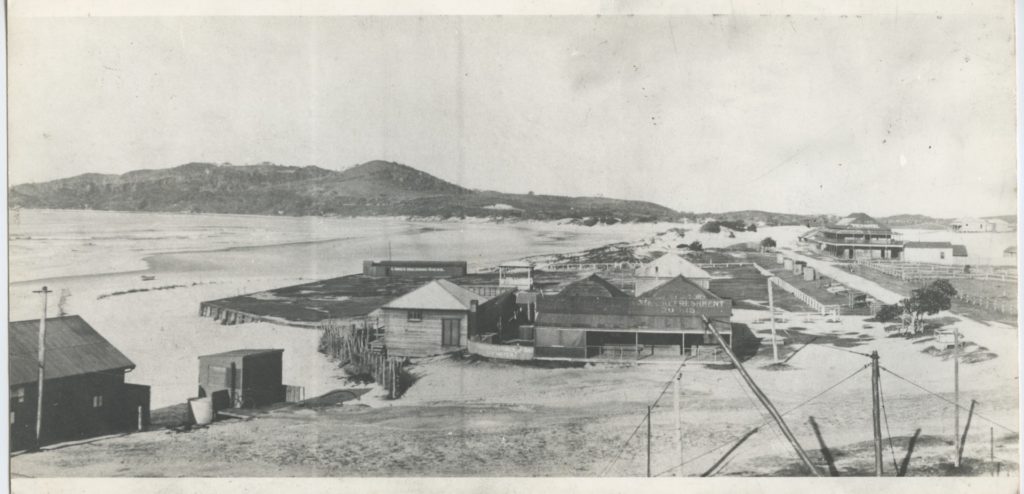

Land was made available for the jetty completed in 1888 and for the railway line, and station – opened in 1894. Merchants were quick to build and open hotels and restaurants to cater for not just workers and traders but also doctors, visitors and the government officials.

Early Byron Bay Town plan

The first major businesses, such as Norco Dairy Company, saw-millers, shipping companies also acquired large blocks of land in the town for factories, milling, processing and storage. But roads, streets, power and water supply remained rudimentary which in a coastal town built on flat marshland carried its own risks in storms, floods and fire. Nevertheless, the pioneers prevailed and by the start of WWI Byron Bay had become one of the major coastal towns and ports between Sydney and Brisbane. The town’s population is estimated at more than 2300 at that time.

View towards Cape Byron

The early township

Looking east

Site 5

BYRON BAY DEVELOPMENT

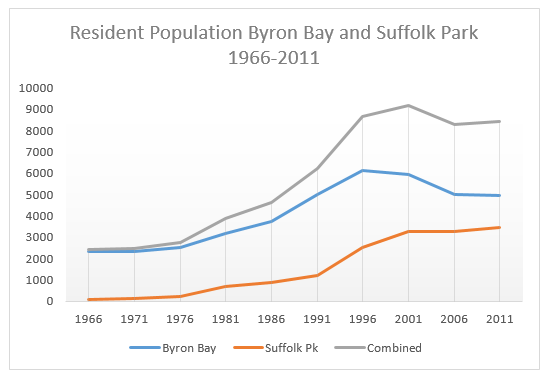

Although there is a record of a single dwelling in the Byron Bay area in 1882, the town was only laid out in 1884 with the first lots sold in July 1886. It was officially declared a town on 28 August 1896.

An influx of farmers, labourers and merchants followed the development of the “old” jetty in 1888, the opening of the railway in 1894 and the building of NORCO’s butter factory in 1895. The town’s population grew rapidly and roughly as its industries developed but stabilised between 2,300 and 2,600 from the end of WW1 to 1971. This half century was Byron Bay’s industrial era when it was unkindly described as a town “reeking with the stench from the piggery, meatworks, whaling factory and sand processing with their effluent colouring the sea and washing on the shore”. All of Byron Bay’s industries had closed by 1975, except the meat works. Cheap houses, clearer air and cleaner seas attracted new people to town.

The two decades between 1976 and 1996 were the “great growth years” for Byron Bay with its population jumping from 2,764 to 8,658. New subdivisions were developed to accommodate demand. The Industrial and Arts Estate of 50 acres was opened for development in 1972 and the nearby Sunrise Beach residential area opened soon after. The “Sandhills” sub-division was opened in 1974 in the area behind Main Beach between Middleton and Massinger Streets. The first land release in the Pacific Vista Estate was made in 1980. Suffolk Park’s boom started in the mid 1970’s with the number of residents jumping 184% in the five years from 1976.

In the twenty years from 1976 the demographics of the Byron Bay changed fundamentally. Industrial workers were replaced by those in the service industries, particularly tourism, and those who sought beach or bush lifestyles. The remaining locals, the newly-arrived surfers, hippies, environmentalists and those looking for a peaceful and beautiful place to live all valued the natural assets and beauty of the area. They understood that the town and its hinterland needed assistance and time to recover.

Byron Bay’s population continues to grow in the 21st century but more slowly.

Site 6

JETTIES

Look across the beach and the surf toward Julian Rocks. Now look at the image below. What is missing? There is no jetty with a ship alongside. This “old” timber jetty built in 1888 extended nearly 400 metres into the sea. Cedar logs were the main freight loaded from it initially but soon included dairy products, bacon, beef, sugar and bananas. By the mid 1890’s Byron Bay had also become the principal passenger port on the North Coast. Horses and then a small railway engine (the “Green Frog”) pulled cargo wagons and passenger carriages along the jetty to and from the ships.

Old Jetty (Source RTRL)

As larger ships began to load and unload this “old” jetty proved too short and the water too shallow to safely moor them. This was made clear emphatically in 1921 when the Wollongbar attempting to clear its mooring at the jetty became grounded and was wrecked on the beach. With completion of the “new” jetty in 1928 the “old” jetty was no longer used except as a platform to fish from. It was demolished in 1947.

Sunrise over the old jetty late 1930’s (Source EJW photo RTRL)

The “new” timber jetty located well to the west of town extended 650 metres out to sea from Belongil Beach and ended in 20 metres of water. The last 125 metres was widened to accommodate two large travelling cranes used to load ships on both sides of the jetty and to lift fishing boats from the sea onto the jetty for servicing and safety.

New jetty (Source RTRL)

In February 1954 huge waves generated by a severe cyclone destroyed 200 metres of the seaward end of the “new” jetty as well as the two large cranes. This damage section was not repaired and the cranes were not replaced. Byron Bay’s 66 years as a significant port were over.

The Green Frog railway engine hauling a whale to the factory. (Source EJW Photo – RTRL)

When whaling began in 1954 the end of the “new” jetty was modified so whales could be hauled from the sea on to its deck and transported to the nearby processing works. Whaling ceased in 1962 and after further storm damage in 1963 the “new” jetty was closed. It was demolished in 1972.

Site 7

SAND MINING

If you were standing here in the mid 1960’s there was no foreshore park, walkway, Lawson Street or buildings. Dunes and swamp extended inland as far as Marvell Street and the sports fields. Only after the area was mined for rutile and zircon in 1968 was the land developed as you see it now.

In 1934 Zircon Rutile Limited (ZRL), was formed in Byron Bay. This was the first company in the world to recover zircon and rutile commercially from beach sand. Mining started in January 1935 at Seven Mile Beach. Initially “black-sanders” manually scraped, dug, concentrated and stockpiled the heavy, black sand. They were paid $4.80 for a 44-hour week, lived in tents near the beach and kept all gold, platinum and tin.

ZRL processing plant

The concentrates were transported to ZRL’s treatment plant on Jonson Street in Byron Bay. In 1943 ZRL became the first company in the world to produce separate, high-grade rutile and zircon from mineral sands. These were bagged and exported from Byron Bay to the world. The zircon was used in the foundry, ceramic and enamel industries. Rutile was used to make white pigment, for paint and plastics, and titanium metal.

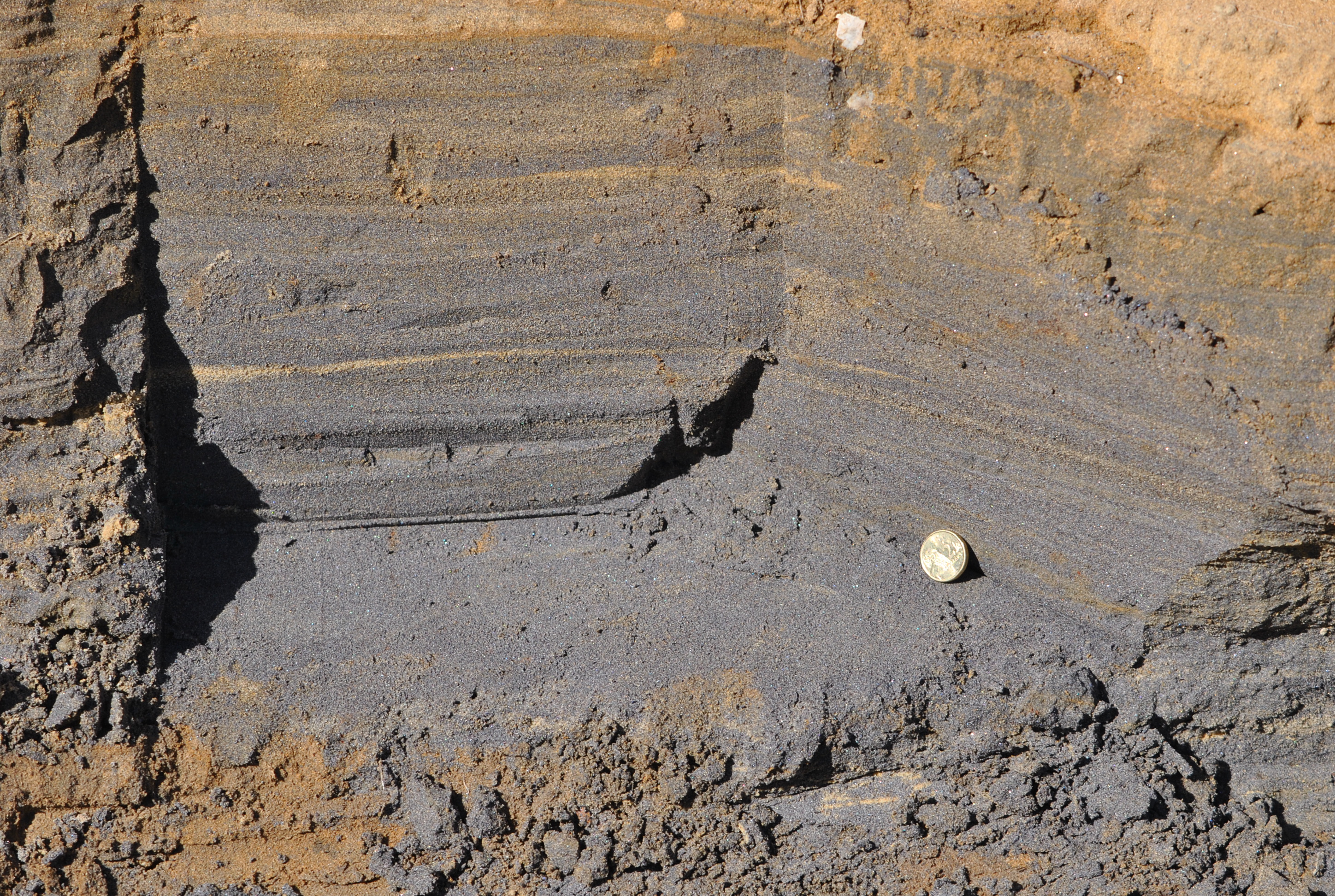

Black sand “lead” containing zircon and rutile

In 1947 mining commenced on Tallow Beach at Broken Head and ended up at Cosy Corner beneath the lighthouse.

Mining moved inland, and in the 1960’s to Main and Belongil Beaches.

In 1948 floating suction dredges, which separated the heavy minerals simply and cheaply from other sandgrains, were introduced. The heavy minerals were pumped to the treatment plant. The rest of the sand remained at its source.

In 1951 ZRL began rehabilitating, reforming and replanting the mined areas; but not always with native species.

Environmental opposition to sand mining grew.

Sand Mining on Main Beach in 1967. RTRL Photo.

Mining ceased in 1968; processing in 1972. Some mined areas are now incorporated in Arakwal National Park; some are public places and some contain private houses, commercial buildings or infrastructure.

After 38 years and production of more than half a million tonnes of premium mineral sand products from its beaches and dunes worth more than $500 million today Byron Bay’s pioneering role in this industry was over.

Site 8

WHALING

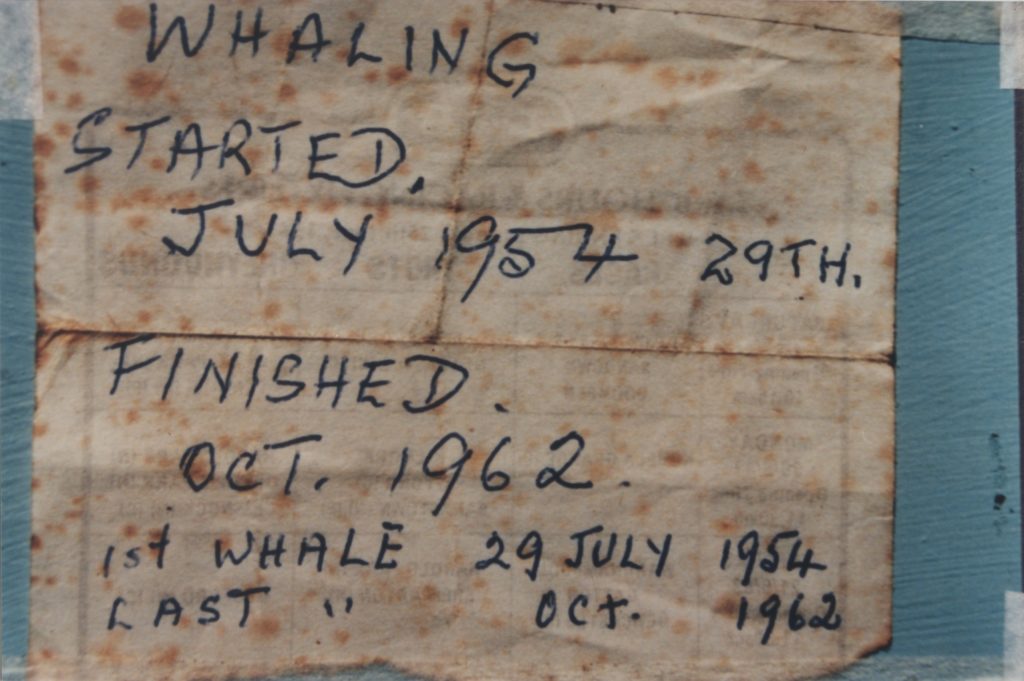

Whaling commenced in Byron Bay in 1954. The Byron Whaling Company with an initial quota of 120 male humpback whales each year “took” its first whale on 29 July that year.

Whales migrating north during May-August from Antarctic feeding grounds to their Coral Sea birthing and mating areas were preferred as they had the largest reserves of blubber then. Whales were leaner on their return journey in September-November having not have eaten since leaving Antarctica. Taking females and calves was prohibited.

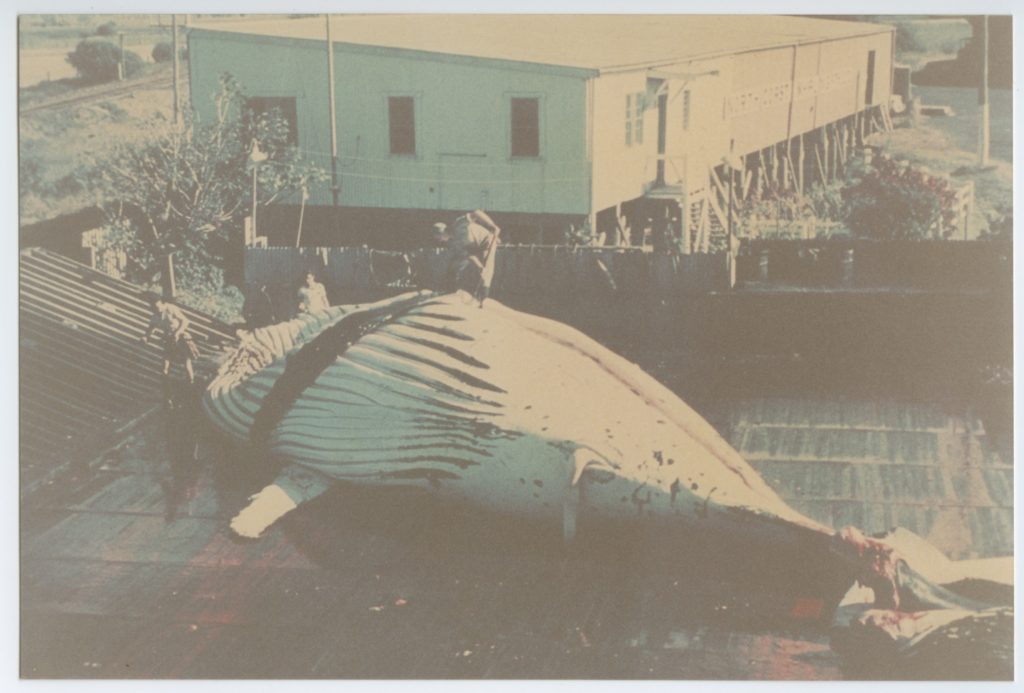

After harpooning and killing the whales the carcass was filled with air to stop it sinking and then towed back to the “new” jetty where it was hauled from the water, placed on a flat top rail wagon and carried to the processing factory.

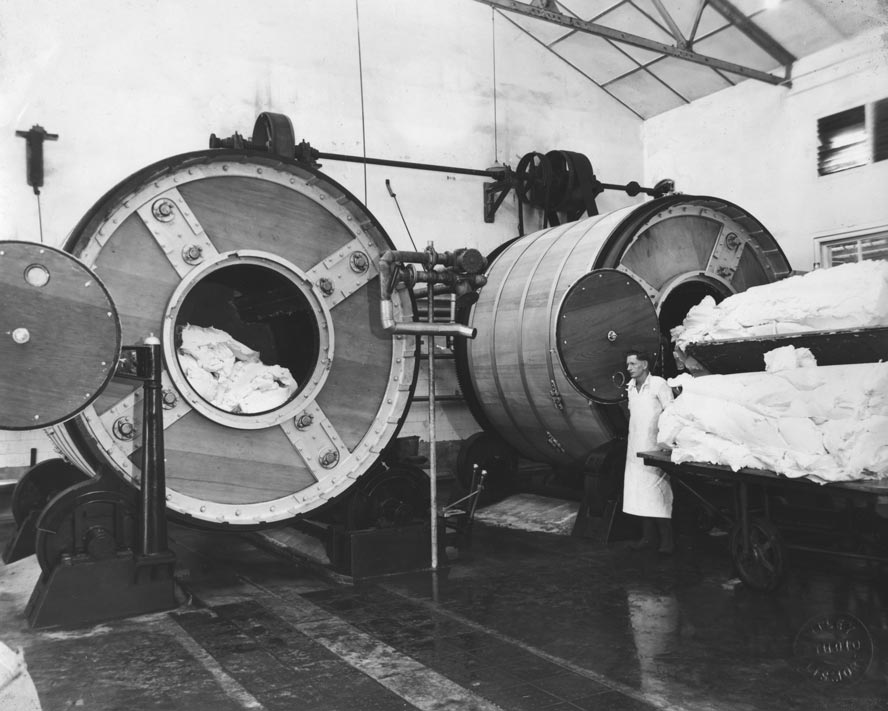

Flensers removed the blubber, skin, and meat. The skin and blubber were boiled to separate the valuable oil (about 10 tonnes per whale) used to make margarine, explosives, cosmetics, lubricants and detergents. The meat was frozen and exported.

Byrond1 bringing a whale back to the jetty (Source RTRL)

After the oil was removed from the bones they and other solid waste were converted to dry “meal” for animal feed or fertiliser. Liquid waste was pumped to sea through a “blood pipe” – hence the many large sharks in the Bay.

Initially many large whales passed close to Cape Byron. On “good” days the whalers Byrond 1 and Byrond 2 would harvest three or four whales.

Flensers prepare a whale for processing (RTRL photo)

But as seasons passed they spent more days at sea, sailing further away from Cape Byron to locate their prey. The whales “harvested” became smaller and leaner each year. In 1962 only 107 whales were captured in 144 days of hunting yielding just 5.9 tonnes of oil each compared to 1959 when 150 whales captured in 56 days 9.7 tonnes of oil each. This was unsustainable economically and ecologically and the Byron Whaling Company ceased operations in October 1962 after harvesting 1124 whales.

In 1962 fewer than 5000 humpback whales remained in the southern oceans. In 1966 the whaling industry collapsed. The humpback population is still recovering with 35,000 expected to pass Cape Byron on their annual migrations.

Whales (Source Craig Parry)

Site 9

AGRICULTURE

Agriculture was the economic foundation upon which Byron Bay was built. The first commercial crop grown was sugar cane processed at a small sugar mill at Ewingsdale from 1887. In 1890 farmers switched to more profitable dairy farming with production underpinning the NORCO Byron Bay butter factory built in 1895 at the southern end of Jonson Street. It primarily produced butter for export to Sydney and ultimately to global markets. By the 1920’s 25% of NSW’s milk production was processed at Byron Bay and by the mid 1930’s Byron Bay was producing 35,000 tonnes of butter annually or 60% of NSW’s total. It continued to dominate the States butter production until the 1960’s.

Norco (Source RTRL)

A few years after the dairy factory was built, a piggery was established in Byron Bay with the animals fed the skim milk and by-products from the dairy factory. This was the basis for the large bacon, ham, sausage and small goods industry that was part of NORCO’s Byron Bay business.

NORCO’s butter factory closed in 1972 and its bacon factory in 1975.

Large butter churns – 1950s (Source EJW photo RTRL)

Bacon sides and hams hanging in the smoking room – 1950s (Source EJW photo RTRL

Bananas, a significant early crop, became important following WWI with annual production reaching 200,000 cases in the 1930’s climbing to a peak in the 1960’s then declining to current low levels.

Byron Bay’s first beef processing meatworks was established just before WWI but did not become a significant producer in the early 1930’s, exporting to Sydney markets and to Britain. From 1959 boneless beef was exported to the US market. Beef production peaked in 1964 and declined steadily until 1983 when the meatworks was closed.

That marked the end of Byron Bay’s 90 year “butter-bacon-bananas-beef” agricultural era.

Macadamia nuts, coffee and other speciality fruits, vegetables and animal protein are the main agricultural products now.

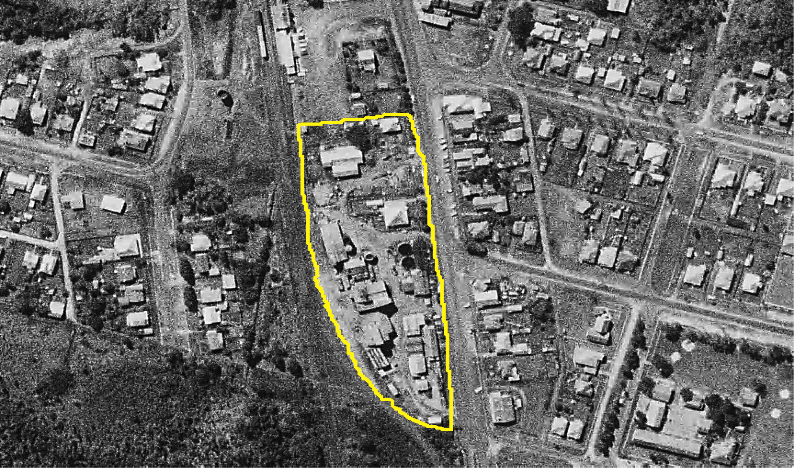

Norco factory site 1960s (Source EJW RTRL)

Sunnybrand Chicken started in the early 1970s as a chicken processing plant employing 3 people handling 200 chickens per day. It quickly grew into one of Byron Bay’s largest industries employing upwards of 400 people capable of processing 300,000 chickens per week and had an annual turnover of $100m.

After 30 years as a locally owned and managedoperation, it was sold to a major Australian chicken processor before being on sold to an American company who closed the operation in 2016.

This marked the end of Byron Bay’s industrial era

Site 10

CEDAR-GETTERS

Until the 1860’s the Byron Bay area was covered by sub-tropical forest; part of the “Big Scrub”. This diverse forest contained huge trees, bushes, vines, ferns and plants that had adapted over the last 25,000 years to a warming, post ice-age climate. It supported an abundance of birds, animals and fish and provided shelter, food and significant places for the local Arakwal Aboriginal people.

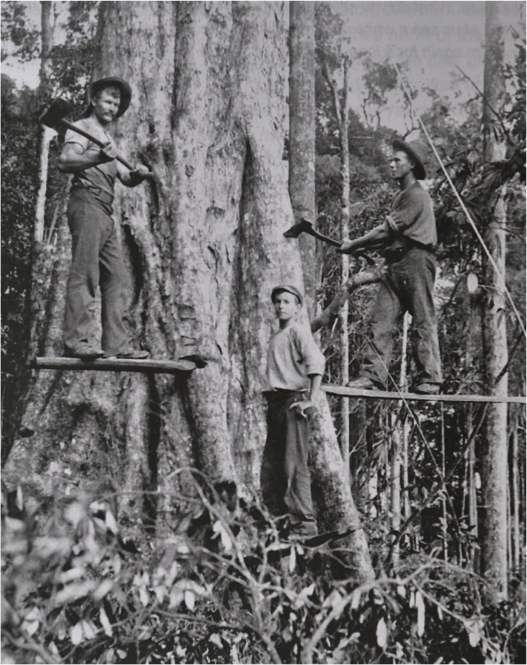

Cedar cutters (Source RTRL)

The first cedar-getters arrived in the area in the late 1850’s with the first camps in the Byron Bay area recorded in the late 1860’s. They and their aboriginal scouts sought the large, straight-trunked, cedars that yielded beautiful, hard, red, termite-resistant wood. They stood on springboards notched into the trunk above the buttress roots to reach the clean straight trunk. Using axes and saws it took several hours of very hard work before the giant would fall. The branches were removed, the butt branded and the log was transported to the coast. Either bullocks “snigged” the log to the coast or it was rafted down the rivers.

Bullock teams (Source RTRL)

At Byron Bay logs were “surf-loaded”. Bullock teams towed them out through the surf either at “The Pass” or “Cosy Corner” to be winched to and loaded on ships anchored close to the beach. They were then transported to the timber markets of Australia and the world. From 1888 logs were loaded on to ships moored at Byron Bay’s “old” jetty and after 1894 could be transported to markets by rail. The first sawmill in Byron Bay built in 1891 converted logs into more valuable timber. In 1908 the export of logs ceased and timber exports became insignificant after WW1. Many cedar-getters cleared land and became farmers.

The impacts of the cedar-getters on the forests and eco-systems of the “Big Scrub” are obvious. As the first Europeans to make significant contact with the local Aboriginals, they impacted significantly their health, culture, community structures, and traditions.

In the 1980’s parks and reserves were formed to protect remaining forest and allow regeneration.

Site 11

FISHING

From 1888 when the “old jetty” was completed fishermen in small boats commenced commercial fishing in Byron Bay; initially for local sale then later for export to Australian markets. During the “mullet run” spotters on Cape Byron would relay the location of the migrating fish to the waiting fishermen who ran their nets around these huge schools catching tonnes of fish in a single haul. The fishermen dragged their bulging nets up onto the beach, often allowing locals to “help themselves” before selling the remainder to the processing plant. From the early 1920’s their catch was processed at the first commercial fish processing plant in Fletcher Street which sold “fresh,” iced, canned and smoked fish.

A large haul of fish on Clark’s Beach -1920’s. (Source EJW RTRL

After WW2 newly identified prawning areas, reef fishing spots and schooling sites provided greater fish variety (bream, tailor, snapper, perch jewfish – all caught on handlines), a longer season, larger catches and improved economics. This catch was processed at the new Byron Bay Fisherman’s Cooperative depot in Lawson Street.

When the “new jetty” was completed in 1928 the fishing boats used it as a base. Their boats were hauled on to it for servicing and protection in severe storms. Prior to the cyclone of February 1954 the fishing fleet was hauled onto the jetty out of harm’s way but this major storm destroyed much of the jetty and 23 of the 32 fishing boats.

Fishing boats on the jetty (Source RTRL)

The jetty was never repaired and without this shelter most of the fleet relocated to the Brunswick River but their catch was transported to and processed at Byron Bay until 1964. The last commercial fishing boats left Byron Bay in 1966.

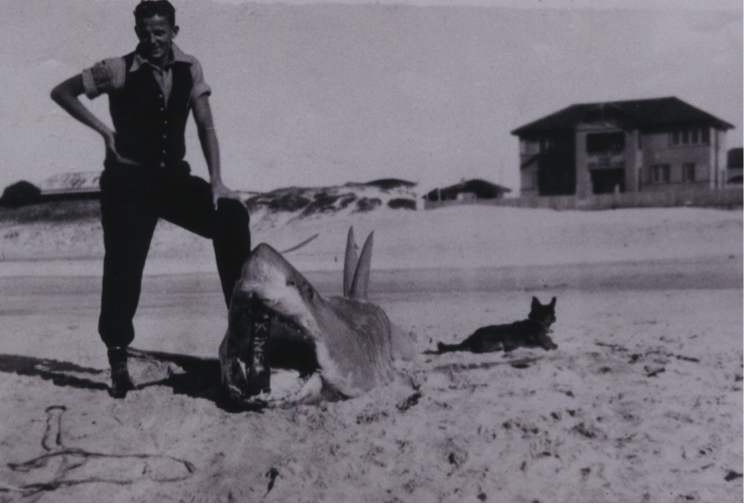

Shark caught in front of the Surf Life Saving Club

Recreational and sport fishing from beach, jetty and boats have been an important part of local fishing history. Many large sharks were caught from the jetties and the beach. Keen amateurs have launched their boats from the ramp at “The Pass” for nearly 100 years; releasing and retrieving their boats through the surf.

Site 12

FIRST PERMANENT RESIDENT

An 1865 account records no white settlers’ dwellings in the Byron Bay area. But by the late 1860’s the first cedar-cutters were operating in the Byron Bay area and gold miners arrived in September 1870. Their numbers grew during the 1870’s but they lived in temporary tent camps or bark huts moving frequently following the timber or gold.

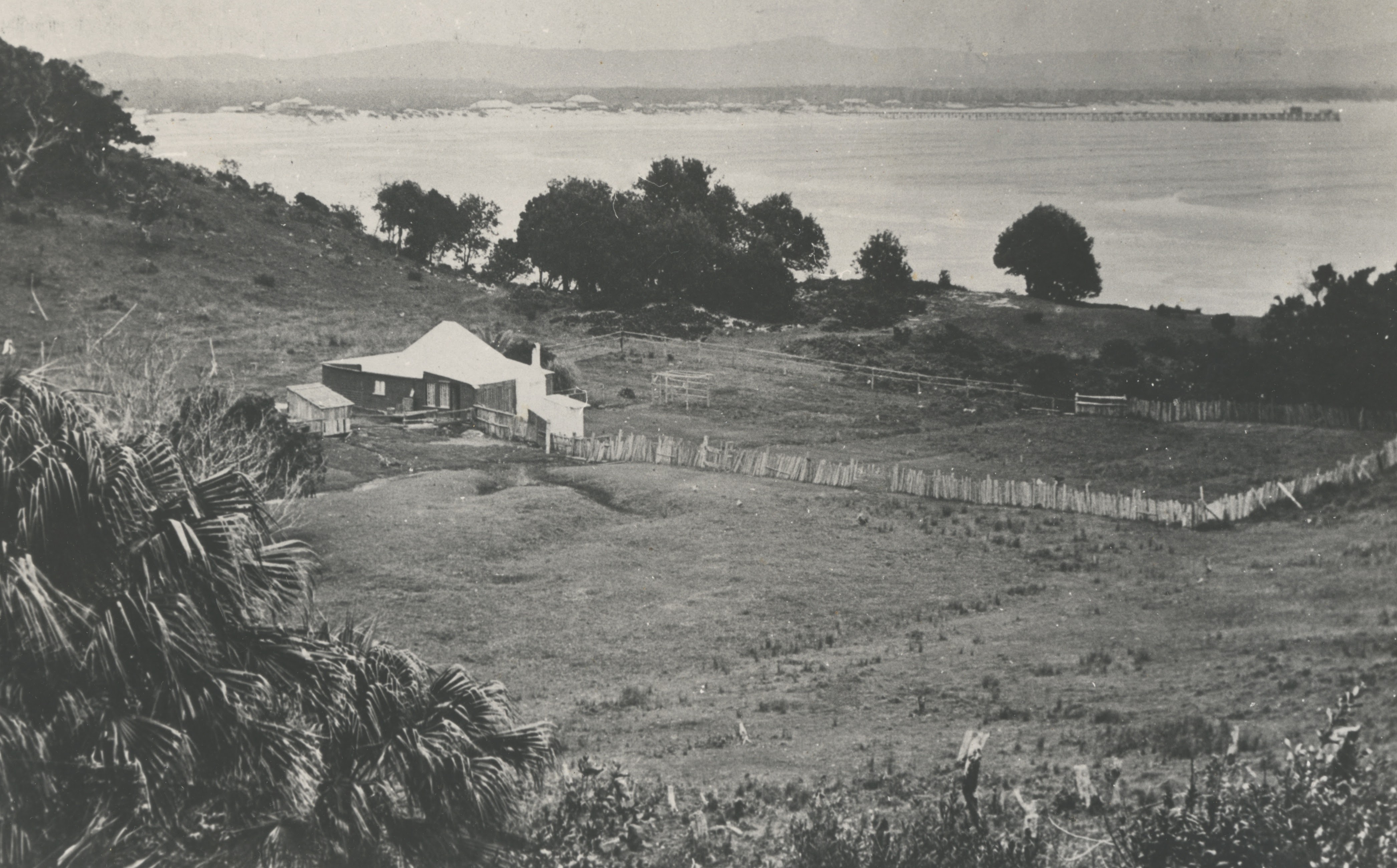

Although there is a long history of Aboriginal occupation and use of land at Byron Bay, such as the 900 year old shell midden at “The Pass”, the first permanent white dwelling in Byron Bay dates to 1883 – at Palm Valley the flat area behind the carpark at The Pass. It was a timber slab building erected by David Jarman, probably in 1882.

First described as a hut, very soon after it became a hotel and accommodation house and Jarman had become the

first white resident in Byron Bay. Jarman selected the Palm Valley site as it was one of few permanent fresh water sources close to shore. Also this corner of the bay was the most sheltered and safest place to land small boats bringing people and goods ashore. He provided`surf boats for ferrying people and goods between ship and shore for the first farmers and the gold miners. Until inland tracks and roads were built in the mid 1880’s all land travel between Ballina on the Richmond River and Brunswick Heads on the Brunswick River was along the beaches. As the shortest crossing between Main Beach and Tallow Beach was from Palm Valley to Cosy Corner all travellers passed his door. The cedar-getters launched their logs into the sea at The Pass or Cosy Corner to be towed by row boats to waiting ships. Jarman provided meals, drink and accommodation for travellers and sailors; and stores and liquor for the cedar-getters, gold miners and first settler-farmers. However, his construction was illegal, erected on land reserved from selection and settlement and if he was selling alcohol it was without a licence.

The building was destroyed by fire in 1934 long after Jarman had sold it in the mid 1880’s. Jarman licenced the Byron Hotel in 1886 and the Pier Hotel in Byron Bay town in 1888 just shortly before the first jetty was completed. He became the first President of the Byron Shire Council in 1906; and died in May 1908.

Site 13

COASTAL CONSERVATION

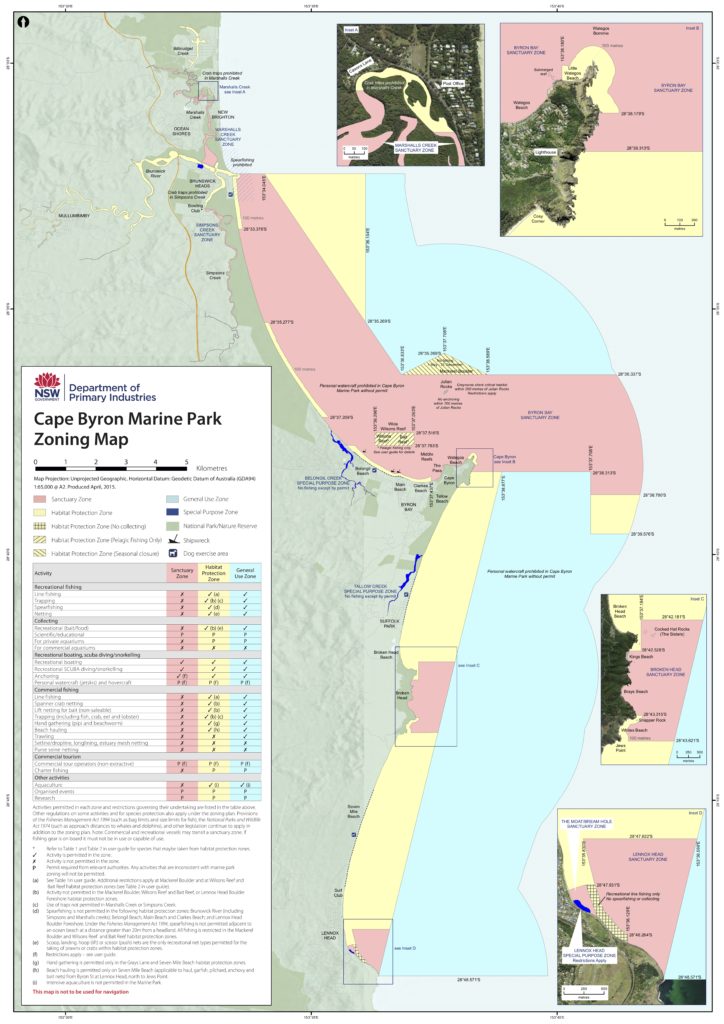

Starting in the early 1980’s the Byron Bay community began establishing nature reserves, national parks and marine parks to protect areas of coastal environmental significance. Now more than 50% of the combined land and sea area stretching five kilometres either side of high tide between Brunswick Heads north of Byron Bay town and Lennox Head south of the town is incorporated in parks and reserves.

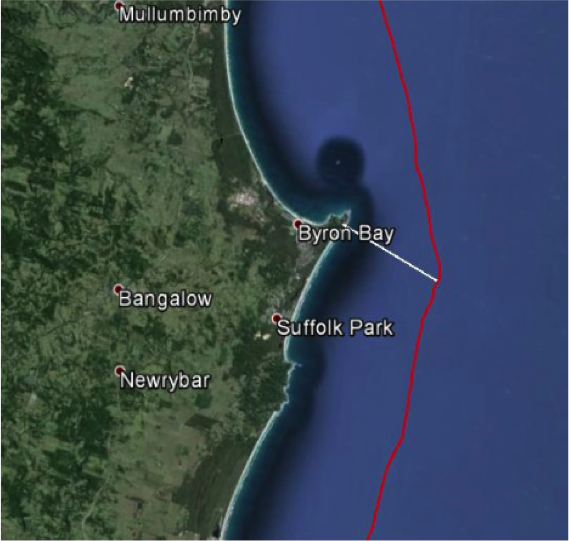

The largest protected area is incorporated in the 22,000-hectare Cape Byron Marine Park established in November 2002. It extends for three nautical miles (5.55km) from mean high water level and includes the sea bed. It is divided into four zones: habitat protection, sanctuary, general use, and special purpose zones. Recreational and some commercial fishing are allowed in the Park.

The Park includes rocky, sandy and coral sea-bed, small rocky islands, exposed and sheltered beaches, riverine estuaries, coastal creeks and lakes. It provides a “safe home” for many species of sea-mammals, fish, seabirds, shellfish marine plants and protects threatened species such as little terns, grey nurse sharks and sea turtles. Humpback whales come close to the Park’s shores on their annual migrations.

The Julian Rocks Nguthungulli Nature Reserve, established in 1961 and popular with divers and snorkelers, and sites of cultural significance to Indigenous people such as Julian Rocks(Nguthungulli), Cocked Hat Rocks(Three Sisters Rock), Cape Byron and beaches around Broken Head as well as Arakwal National Park are included in the Park.

There are five land Nature Reserves covering 1310 hectares in the Byron coastal area (Marshalls Creek, Brunswick Heads, Tyagarah, Cumbebin Swamp, and Broken Head). They incorporate coastal sub-tropical forest, wetlands, salt marsh, dunes, coastal heath, swamps and riverine environments.

The Cape Byron State Conservation Area of about 98 hectares represents the remnants of the Cape Byron Headlands Reserve created in December 1885 to protect native flora and for recreation purposes. This 1885 initiative provided the model for coastal environmental protection actions of a 100 years later that created the reserves and parks in Byron’s coastal areas residents and visitors value and enjoy today.

Site 14

WATEGOS BEACH

The area now known as Wategos Beach, but originally called Little Beach, was incorporated in a Reserve in the initial classification of land at Cape Byron and so was unclaimable by settlers. However, after a change in classification in 1933 three six-acre blocks on the beach were gazetted and sold to private individuals. Murray (Mick) Watego, son of a native of the Loyalty Islands and an English mother, and who was a WW1 veteran acquired the westernmost of these blocks. Murray, his wife and their ten children cleared the land and grew bananas and vegetables for sale locally and for export. With time the beach and area became known as Wategos. These leases expired in 1960.

In 1961 the Byron Shire Council surveyed and gazetted a 25-acre residential development at Wategos Beach. Approximately 86 blocks were available for auction on 25 November 1961 at a cost of about $700 (or about four months average wage at that time). However, for many blocks no bids were received, the perception being that they were too far from the town centre and had poor access. A further six auctions were required (July 1964, June 1968, January 1970, January 1971, September 1972 and May 1973) before all the blocks were sold.

Layout of Wategos subdivision 1962. Names of bidders added. (NSW Govt Map.)

It took more than 30 years after the initial 1961 auction before most of the Wategos blocks were built on. The three air photo images below, taken in 1958 1966 and 1987, show the initial slow development of what is now one of the premier and iconic beach-side living precincts in Australia.

Watgeos from the air

Site 15

CAPTAIN COOK

On 15 May 1770, Captain James Cook sailing up the east coast of Australia in the Endeavour passed the eastern most point of the Australian mainland. He named it Cape Byron after Captain John Byron RN who sailed around the world in the Dolphin in 1764-1766.

Cook’s log for 15 May reads “…. As soon as it was daylight we made all of the sail we could …. At noon we were by observation in latitude 28o 39’S and longitude 206o 27’W….. A tolerable high point of land bore northwest by west a distance of 3 miles. This point I have named Cape Byron. It may be known by a remarkable sharped peaked mountain lying inland northwest by west from it…..”

From this description Endeavour’s location can be calculated. It was about 5.6 km southeast of Cape Byron lying off Tallow Beach.

The “remarkable peak” is now Mt Warning(Wollumbin).

Joseph Banks, botanist on Endeavour, records sighting aboriginal people in his journal of 15 May, “…..we observed them with glasses for near an hour during which time they walked upon the beach and then up a path over a gently sloping hill, behind which we lost sight of them. Not one was observed to stop and look toward the ship: they pursued their way….”

It is probable that the aboriginal people were walking along the southern part of Seven Mile Beach.

No one from the Endeavour landed in Arakwal or Bundjalung country that day. Cook sailed on northward claiming all of the east coast of the continent for England and naming it New South Wales. But his voyage was a harbinger of the arrival of the first European settlers to Australia in 1778.

Replica of the Endeavour

Site 16

SHIPWRECKS

Ships were the only effective transport along the Northern Rivers coast until the railway arrived in Byron Bay in 1894 but there is no safe natural harbour along this coast. Byron Bay was identified as the safest deep-water anchorage. A deep, artificial sea-port protected by a five-metre-high break-wall extending from Cape Byron to Julian Rocks and a similar one extending from Belongil Creek toward Julian Rocks was proposed but never built. A timber jetty extending 300 metres into the sea from the end of Jonson Street was completed in mid-1888.

Prior to completion of the lighthouse in 1901 more than sixteen wrecks and the loss of many lives occurred along the Byron Coast. Perhaps the luckiest survivors were the two passengers from the Swift who were cut from the overturned hull on the beach by passers-by after it ran ashore south of Brunswick Heads.

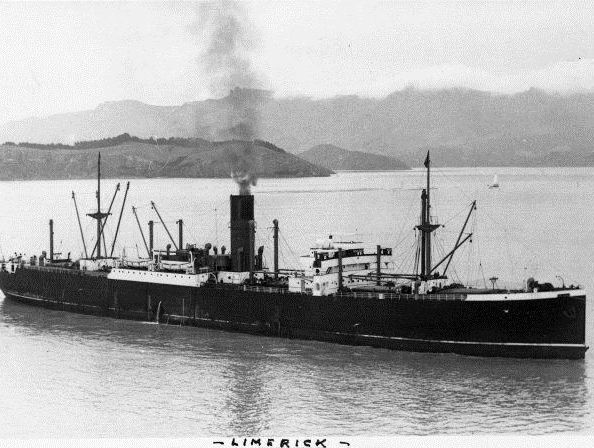

But the most famous wrecks at Byron Bay were of the Wollongbar in May 1921, the Tassie III in June 1945 and the torpedoing of the Limerick and the Wollongbar II by a Japanese submarine in April 1943.

Early in the afternoon of Saturday 14 May 1921 the fully-laden Wollongbar was tied up alongside the old jetty about 200 metres offshore. It was ready to board crew and passengers for departure to Sydney at 5.00pm. In the large waves, strong winds and low tide the ship’s keel began bumping the seabed. The captain cast off to head into deeper, safer water. However, as the moorings were freed the ship grounded on a sand bar and turned broadside to the large waves. Several times the vessel’s bow was turned back toward the sea but each time the ship encountered the sandbar, stalled, and was pushed closer to land. Eventually the wind, waves and current prevailed and the ship stranded in the surf on Belongil Beach with no lives lost. Its cargo of butter, bacon and bananas was off-loaded or jettisoned.

The Tassie III, a 120 tonne, steel ship requisitioned by the US Army and carrying condemned ammunition came into Byron Bay on the night of 8 June 1945 to anchor from a storm. During the night the ship dragged its anchor and beached. Next high tide the ship refloated and washed up against the “old jetty”. In the rough weather the Tassie III broke the jetty piles, the stumps penetrated the hull and the vessel sank with all munitions ion board.

Wreck of the Tassie III against the jetty in 1945. (Source Byron Shire News)

The closest enemy attack to Byron Bay in World War II was the torpedoing and sinking of the Limerick 32 kilometres off Cape Byron by Japanese submarine I-126 on 26 April 1943 in WWII.

MV Limerick (Source Northern Star)

All but two of the 72 crew survived.

On 29 April 1943 the Wollongbar II, the sister ship of the Wollingbar, was torpedoed and sunk south of Byron Bay by Japanese submarine 1-180. Two torpedoes hit the ship in quick succession breaking it in two. Both pieces sank within minutes giving those on board little chance of escape. Only five crew of 37 survived. The captain and many others that died were from Byron Bay.

But it was the cyclone of February 1954 that destroyed the greatest number of vessels when 23 of 32 fishing boats hauled onto the “new” jetty out of harm’s way were wrecked as the storm destroyed much of the jetty. That cyclone also marked the end of Byron Bay as a port.

Site 17

LIGHTHOUSE

Lighthouse 1920 (Source RTRL)

With many ships wrecked close to Cape Byron, increasing north-south shipping along the east coast of Australia and the growing importance of Byron Bay as a regional port a lighthouse was built on Cape Byron at the start of the 1900’s. The first light shone on the evening of 1 December 1901.

It is the brightest of all lighthouses on the Australian coastline with the light visible 40 kilometres away. Initially the light was generated by burning kerosene on six wicks (145,000 candela). In 1914 this was changed to burning vaporised kerosene on a single mantle (545,000 candela), then to triple mantles in 1922 (1 million candela) then to an electrically powered 2250-watt bulb in 1959 (3 million candela), a 1000 watt quartz halogen light in 1976 and to an LED light in 2015.

The light is beamed through a bivalve Fresnel lens made of glass prisms manufactured in France. The lens floats in a circular trough of mercury for stability and ease of rotation. The original rotating mechanism was manually wound up several times each night.

The flash sequence of the lighthouse is unique flashing for 0.3 seconds every 15 seconds, every night of the year. The light still shines every night- less as a navigational aid in this age of GPS and more as an iconic link to the past.

Three lighthouse keepers lived in three cottages on the site but three keepers became two in 1959. The last solo keeper departed in 1989 when the operation was automated. Their well-kept cottages can be rented out now but spare a thought for those early keepers as they spent all night every night keeping the light shining.

“Olim periculum nunc salus” etched on the glass doors to the lighthouse translates from Latin as “Once dangerous now safe”. A fitting motto for this powerful lighthouse that since 1901 has guided ships around the easternmost point of the Australian mainland.

The site is now under the responsibility of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and the National Parks and Wildlife Service of New South Wales.

Lighthouse on Cape Byron (Source Craig Parry)

Site 18

GOLD MINING

In March 1870, prospector John Sinclair recovered twelve ounces of gold in two weeks from the

beaches at the mouth of the Richmond River at Ballina. News of his “ounce per day” discovery soon

spread and by September gold had been found on Seven Mile and Tallow Beaches, south of Cape Byron

and on Main Beach. The entire coastal strip, except for a reserve between Belongil Creek and Tallow

Creek was pronounced a goldfield. Gold occurred as small grains in black sand “leads” on the beach and

in the dunes behind the beach.

Black sand “lead” from Seven Mile Beach. Main Photo

The “black-sanders” working in groups of thThe “black-sanders” usually working in groups of three, skimmed or dug black sand from the “leads” until enough was stock-piled for processing. One then shovelled the black sand into a hopper, one pumped water to wash the sand over mercury-coated, copper plates and down a sluice box, and one removed the black sand “tailings”. It was hard, monotonous, unrelenting, physical work. Beach.

The fine gold amalgamated with the mercury on the copper plates to form “amalgam” a putty-like alloy which was

scraped from the copper plates. The “amalgam” was placed inside a pumpkin or potato, which was then placed on a shovel and roasted in a fire. The mercury vapour condensed in the outer layers of the burnt vegetable. This was crushed and panned to recover the mercury for re-use. The gold would remain on the shovel as grains or as a “button” if the fire had been hot enough to melt gold.

Fine beach gold – recovered after retorting. Main Photo.

By 1890 the richer deposits had been worked out. Only a few prospectors stayed seeking their fortune. This gold-field was known as the “poor man’s diggings.” Everybody found some gold but no one made a fortune. The yield for a successful miner was between a half and one ounce of gold per week. Total production is estimated at 20-30,000 ounces. In later difficult economic times and the 1930’s depression the unemployed and desperate returned to earn a meagre living from the beaches again.

Site 19

TALLOW BEACH

Do you know why this beautiful seven-kilometre long stretch of sand and surf is called Tallow Beach?

Up until 1864 it was un-named but in that year a large amount of tallow (rendered beef and mutton fat) highly valued at that time to make soap, candles and lubricants was washed up on the shores of the beaches either side of Cape Byron.

It represented the cargo of the 100-tonne schooner Volunteer that was sailing from Baffle Creek in Queensland to Sydney carrying 114 casks of tallow. The ship was caught in an easterly gale as it passed Cape Byron in the night and was driven on to the jagged rocks at the foot of Cape Byron and totally wrecked with the loss of all lives.

Some of the tallow was washed ashore still in the original casks and was later salvaged and “exported” from the beach. The contents of the broken casks floated and came ashore as small pieces and lumps where it melted in the hot sun, coated the sand grains and pebbles then solidified in the cool nights or when covered by sea water until it eventually decomposed. Hence the name Tallow Beach. Tallow is now used to make biodiesel.

Tallow Beach (Source Robert Sampimon)

Until tracks and roads were established inland in the 1880’s this beach served as part of the main coastal “highway” for horse-back travellers between the Richmond and Tweed Rivers. Timber was harvested from the dunes and flat land behind the beach and gold and mineral sands were mined from it.

Two intermittent water courses, Tallow Creek and Ti-tree Creek cross the beach draining tea brown water from lagoons behind the dunes. Ghost crabs build their sand-ball patterns and scurry around at night. Many birds feed and rest on it. A few build their nests on the edges of it. Occasionally large sea mammals are washed up to decompose and provide food for scavengers. Wallabies leave their characteristic tracks in the soft sand. The northern half of Tallow Beach is now included in the Arakwal National Park.

Site 20

ILUA (BUNDJALUNG – ARAKWAL INDIGENOUS LAND USE AGREEMENT)

Native Title and Indigenous Land Use Agreements

The Bundjalung of Byron Bay Arakwal people negotiate with the NSW State Government to settle their first Native Title claim not long after the historic “Mabo” High Court decision in 1992

The Arakwal elders Lorna Kelly, Linda Vidler and Yvonne Graham made the first Native Title Application on behalf of the Arakwal people in 1994.

Their Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) reached in 2001 was the very first of its kind and a landmark agreement in Australia.

It won an International award acknowledging the agreement and the conservation and protection of country. The NSW Government and the Arakwal People were awarded the prestigious Fred M. Packard award for distinguished achievement in wildlife preservation by the International Union for the Conversation of Nature, at the 5th World Park Congress held in South Africa in 2003.

Two more Indigenous Land Use Agreements followed soon after.

Government and Native Title Claimants throughout Australia have used the Arakwal negotiations as a best practice model in their own respective negotiations.

For mor detailed information on these historic agreements please visit the Arakwal website see link below http://arakwal.com.au/